Heimish and homelands: the origins of Yiddish

Rebecca Lyons investigates the evolution of Yiddish, exploring its place within identity, politics, persecution, and contemporary culture.

The evolution of language shares surprising common ground with evolutionary biology: both creature and creole are products of social, cultural and geographical pressures, their variants interacting and interrelating throughout history. During the Middle Ages, an age of flux and mass movement of Jewish populations (throughout a region then known as Christendom) this process was particularly marked. The Jews of the Iberian peninsula, surrounded by speakers of Spanish and Arabic, initially developed a distinct language, Ladino, incorporating elements of these local languages into their Hebrew-based grammar. A similar merging occurred with the Jews of Europe, who developed a Yiddish language; a hybrid of Hebrew and German, with eastern European influences. Yiddish, therefore — of Old High German origin — comprises an entire patchwork of dialects.

Unpicking the details, the language we recognise today has a Rhenish source, infused with these multi-lingual, multi-ethnic elements. This reflects the accretion of vocabulary as Jewish populations spread eastward from the Iberian Peninsula through what is now France and Germany. The Rhine Hypothesis proposes the emergence of Yiddish as a language spoken by French refugees inhabiting the Rhine-Moselle valley during the Middle Ages. Although Yiddish originated in ninth-century central Europe, spoken predominantly by the Ashkenazi-Jewish community, the Yiddish-speaking Rhine population migrated over the following centuries, first settling in German provinces and then moving towards Slavic territories. This cultural collation accounts for the remnants of High German present in Yiddish.

Russian-Jewish linguist, Dr. Max Weinreich, identifies four distinct stages in its inception and development, each spanning several centuries: Early Yiddish (800—1250), Old Yiddish (1250—1500), Middle Yiddish (1500—1750), and New Yiddish (1750—present day). Although no written documents survive from the Early period, Weinreich suggests this primary phase was, in fact, the most important, as it set the precedent for ‘the genesis of the fusion language’. Interestingly, after the cultural and national tensions generated by the Holocaust, Weinreich set out to create distance from these German roots, arguing that Yiddish instead began as a Romance language (i.e. derived from Vulgar Latin, existing in the Italic subgroup of the Indo-European family), and was only later Germanised. It is his belief that the dialect was formed by Jews who arrived in Europe as traders many centuries earlier, later settling in northern France and western Germany.

The history of Yiddish provides us with sociological insight, too. Its development can be seen as a documentation of Jewish responses to persecution and segregation. Movement is traceable through changes in the language. Take the Jewish emigration from the Rhineland following the massacres of 1096 — a series of mob-lead mass murders of Jews by German Christians in response to Pope Urban II’s calling for the First Crusade (1095—1099) — for example. Proclaiming adherence to their Catholic mission, the Crusaders, unhindered by any political authority, attacked Jewish communities in the Rhineland, in what is considered the earliest documented form of organised anti-Semitism. With local courts unable to exercise jurisdiction over vandals, the mob slaughtered Jews without fear of retribution. The bloodshed which arose from fanatical Christians’ religious zealotry drove the Jews eastwards, towards Poland and its surrounding areas, where Yiddish was to absorb its Slavic element.

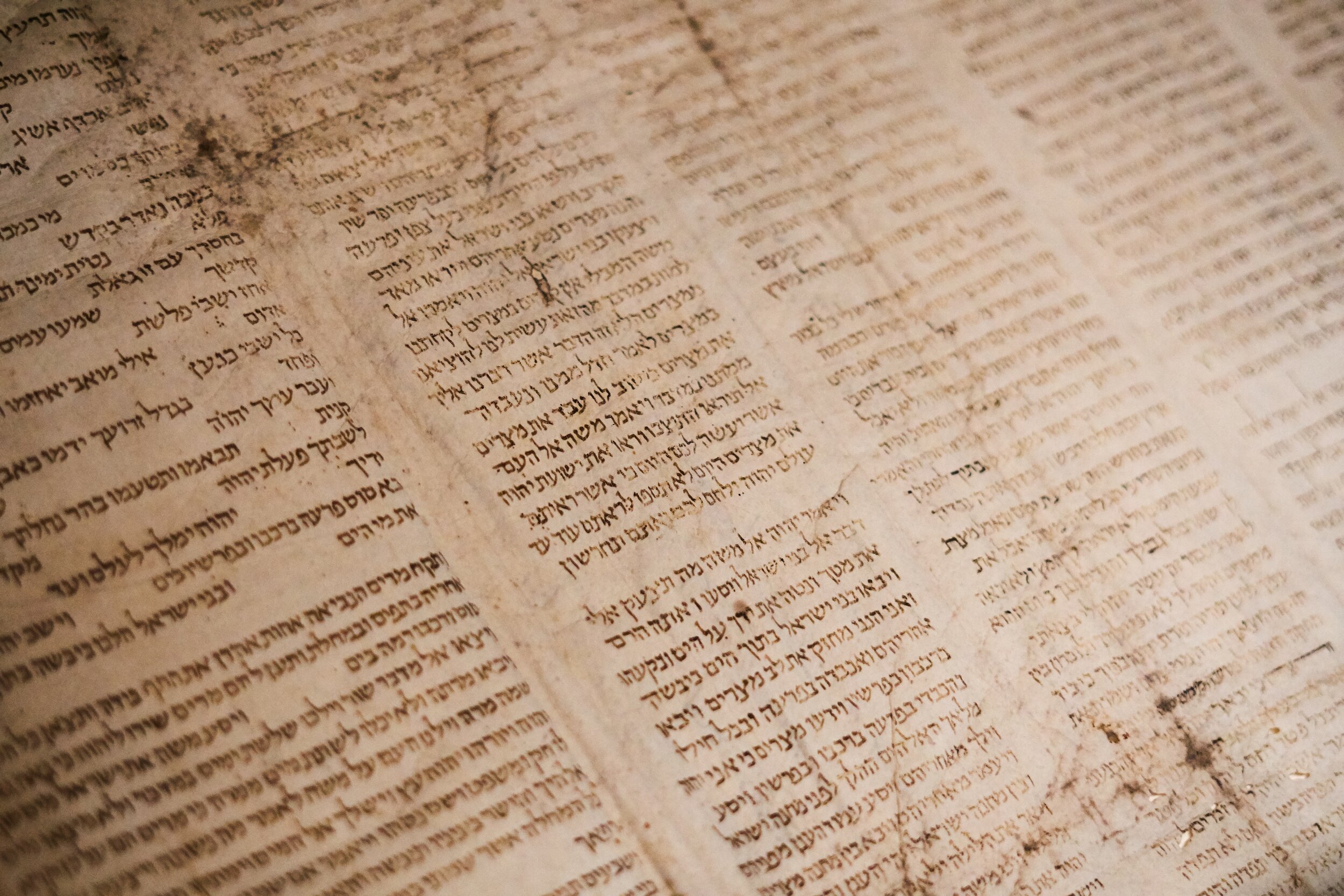

One of the many difficulties encountered by historians tackling the evolution of Yiddish is the near complete lack of surviving documents in the vernacular during the early centuries of Ashkenazi history. This problem is exacerbated by the nature of documents from later centuries, which tend to reflect legal and technical language and concerns, rather than the spoken language itself. German literary language seems to have provided the model for Yiddish texts during this later period. Complicating the researcher’s task further is the multi-directional migration of Yiddish throughout central and eastern Europe. However, although no direct evidence exists to confirm that all branches of Yiddish are traceable to a single ancestor language, Dovid Katz argues that ‘a significant portion of Yiddish in time and space exhibits clear signs of derogation from a protolanguage’.

During the early modern period, Yiddish flourished in the culturally thriving communities of Poland and the Pale of Settlement, where segregation conserved the language of this distinct ethnic and religious population. By contrast, in western Europe, for example Holland and Britain after 1660, Yiddish played a far smaller role in uniting Jewish communities since assimilation and tolerance had dispensed with the need for the ghetto. Yiddish had, by this point, migrated as far as it was to go and was preserved as the cultural badge of eastern European Jewry. Indeed, like the ghetto itself, Yiddish was a means of protecting this religious and social identity during the Enlightenment.

From the early nineteenth century, therefore, Yiddish adopted a role similar to that of Latin, in the Middle Ages, where it served as a ‘lingua franca’; a language and literature that could be understood Europe-wide regardless of the speaker’s native tongue. French and Polish Jews, unfamiliar with each others’ languages, were in this way able to communicate through their shared knowledge of Yiddish, both in speech and writing. Written Yiddish continued to preserve its practice of employing the Hebrew alphabet and right-left textual layout, anchoring the language in this way to its Hebrew roots. However, it was during this time that Jewish thinkers and philosophers began to argue for the abandonment of Yiddish as the language of a persecuted minority, which no longer needed to enclose itself in a linguistic ghetto that made it impossible to access the full benefits of French or German culture (and civic rights).

While this may have had some influence in western Europe, where Jewish communities were rapidly acquiring rights despite continuing anti-Semitism, Yiddish continued to flourish and to produce works of great literary merit in eastern Europe, up until the outbreak of the Second World War. Examples of such works include David Pinkski’s Dos Hoyz fun Noyakh, and Sholem Asch’s trilogy Farn Mabul. The difference between western and eastern Europe is evident in the choice of language of Jewish writers, from both regions. Karl Marx and Franz Kafka chose to write in German, whilst author of the gothic masterpiece The Dybbuk, Shloyme Zanvi Rappoport (more commonly known by his pseudonym S. Ansky) wrote in Yiddish. The historical movement of Jewish people across Europe, taking with them and developing the Yiddish language, effectively ended in the early eighteenth century — at least in the sense that they had reached the outer limit of the regions that they were to settle in.

Whilst Yiddish is a language deeply connected with the process of migration, other social factors influencing its overall development and practical use must be considered. Arguably, the deterioration of Yiddish had roots in the rejection of the language by young nationalist Jewish groups long before the rise of Nazism. Jews who increasingly identified themselves as Varsovians and Poles, preferably spoke Polish, endeavouring to integrate into mainstream Polish society. In the post-war period, following the near destruction of European Jewry and its cultural institutions, Yiddish contracted, to the point where it is now considered a language of primarily historical interest, like Greek or Latin.

Similarly, the flourishing of Yiddish writers and poets after the Russian Revolution of 1917 was short-lived. Although the socialist ideals which replaced tsarist oppression brought about an initial atmosphere of tolerance and expressionism, a resurgence of anti-Semetism under Stalinist rule resulted in the decimation of notable Yiddish-Soviet writers. The murders of authors such as Moshe Kulbak, David Bergelson and Peretz Markish, by exile to the gulags or subjection to firing squads, resulted in the tragic loss of Yiddish literary masterpieces.

Returning to the present day, Yiddish has undergone one more, somewhat unexpected migration, into western contemporary culture. It has resurfaced in both popular slang and cinematography; consider Evgeny Afineevsky’s satirical film ‘Oy Veyy! My son is gay!!’ (2009). Yet, the language predominantly remains the medium of communication for ultra-Orthodox Jews, and has been widely abandoned by secular Jews, either because they simply have no further use for it as a living language, or because its universalising function has largely been superseded by Modern Hebrew. Comparing these two languages is telling: Modern Hebrew flourishes because it is the official language of a nation state, whilst Yiddish, to paraphrase Joseph Roth, like the Jewish people themselves, can be found everywhere and is fully at home nowhere.