In conversation with Jacqueline Campbell

Following her selection as a Schmidt Science Fellow, Emily Hufton interviews Jacqueline Campbell on her unconventional career path, outreach work, the climate crisis, and how she’s navigating the UK coronavirus lockdown.

If anybody is looking for a role model, they should look no further than Jacqueline Campbell. Entering science after eleven years as a tube driver on the London Underground, Jacqueline was recently awarded a prestigious Schmidt Science Fellowship following her PhD search for organic matter on the face of Mars. She now plans to move her sights from the skies to the seas, focusing on ocean acidification to better understand climate change. I caught up with Jacqueline over Zoom, where I was struck by her warmth and her humanitarian approach to many of the big issues facing science today.

Jacqueline’s pathway into STEM was all but traditional – despite her childhood interest in space, she never pursued science. Instead, she took Literature, History, and Media Studies at A-Level and went on to become a tube train driver, working on the London Underground for 11 years. During that time, Jacqueline cultivated her interest in space science, doing correspondence courses with the Open University and an evening course at UCL on astronomy and astrophysics. This helped her to discover her interests (“the planetary side of it, how the solar system evolved, evolution and the animal kingdom”) and areas she claims she wasn’t so good at (“mathematics and theoretical physics”). She eventually enrolled at Brighton University to study Earth and Ocean Science.

Jacqueline speaks candidly about the difficulties of her transition into science, particularly grappling with new technology: “We never had a computer in the house growing up, and by the time I started university everyone else was much younger than me and very well-acquainted with computer stuff and coding ... I also had missed a whole bunch of basic maths.” She didn’t let these factors disadvantage her, even if they mean that she “still [has] to go back and look at things a bit more carefully than other people who went a more traditional route.” Jacqueline says she owes a lot of her resilience to planetary scientist Dr Louise Alexander, whom she met during her undergraduate days and sees as a role model: “a working class, salt-of-the-Earth person who had come back to studying as a mature student, she was incredibly helpful and friendly and kind, always very modest, and always of the opinion that you didn’t have to be some genius to study science.”

Jacqueline emulates this knack of making people feel welcome in the sciences. She is a champion of accessibility, committed to challenging the idea that scientists are middle class, white, and male, and emphasises the importance of role models: “hearing somebody that sounds like you, seeing somebody that looks like you I think is important ... I try to make an effort not to moderate my broad London accent too much when I give talks.” She also does outreach work, including giving a talk at the European Space Agency and working to engage young children with science. The perception of STEM as an elite field, one “that you have to be some kind of genius or special person” to get into, frustrates Jacqueline. This feeds into her ideal of role models: “we tend to use astronauts as examples of ‘Look, look how cool this is’ and it’s like, what are the odds of you becoming an astronaut? Basically zero, but the odds of you becoming a geographer or the odds of you becoming a geologist are actually pretty high, so you can get into space science that way.”

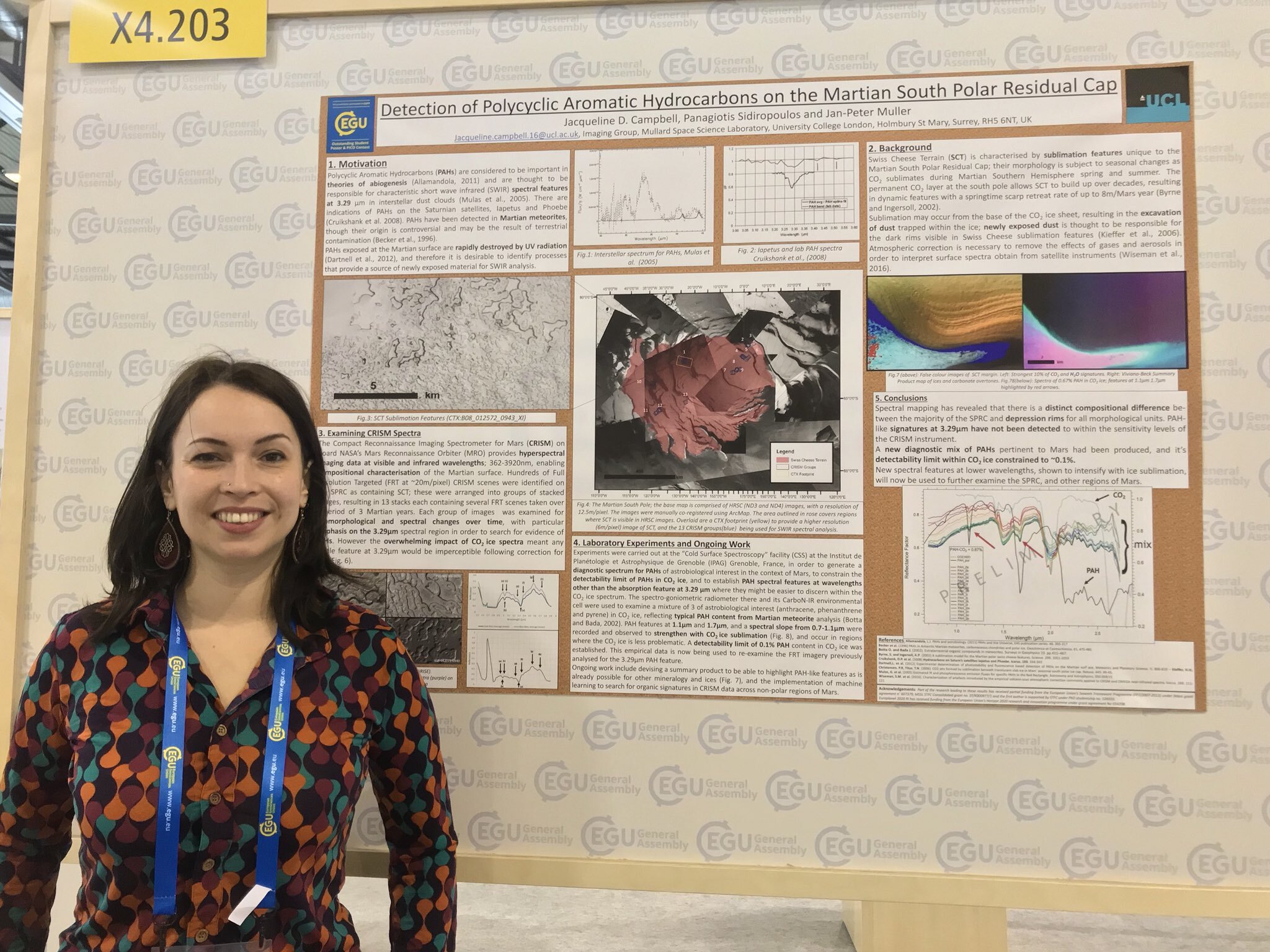

Jacqueline’s PhD work involved looking for organic signatures on the surface of Mars, which she says was quite a challenge: “Mars is quite a hostile environment for anything potentially alive or even the building blocks of life, they very quickly get broken down by ultraviolet radiation on the surface. What I do is look for dynamic features that uncover new material that has previously been buried, and then I can look at that with space satellites to see if that newly uncovered material has got any organic signatures in it. I haven’t found any, but what I have done is some laboratory experiments on the side to establish how much would have to be there for you to find it, so this is establishing the detectability limit.”

Jacqueline’s focus has since shifted to the ocean, which she considers to be “almost like our version of outer space here on our planet, because we know so little about it – it’s very difficult to go and explore there. We know more about the Martian surface than we do about the deepest areas of the sea.” Her work focuses on ocean acidification, which occurs as a result of our seas absorbing atmospheric CO2, lowering the pH: “being able to understand the history of that and model the future of that is a really good metric for climate change.”

Jacqueline is passionate about the issue of climate breakdown, particularly aware of the challenges it poses, “especially to the poorest people in the world, most affected if our sea levels rise or if our fish stocks die out or if there’s problems with biodiversity.” Whilst she acknowledges the role of lifestyle choices, she attributes most of the responsibility to “the governments and the people in charge and the people with money”, who could implement the structural and policy changes needed to empower people to make sustainable choices.

Jacqueline also advises caution: “at the moment you’re seeing a lot of criticism of some countries and their output of CO2 and various greenhouse emissions, but they’re essentially going through the same process that much of Western Europe and North America went through with the industrial revolution, because those countries have been kept in various states of poverty by lots of actions from people in the west.” She argues we should be using “the prosperity we got from using fossil fuels to make renewable energy more affordable and available for everybody.”

Thankfully, the coronavirus lockdown hasn’t prevented Jacqueline from working (her laboratory software is accessible remotely), even if her “productivity has taken a nosedive” just as much as everyone else’s. When asked if she thinks the lockdown will change the way institutions approach research in future, she says yes, and immediately points out that the ability to work remotely is “something that a lot of disabled activists have been campaigning for for a long time.” Jacqueline praises the way that the Open University and Birkbeck operate, particularly compared with some of the other “more traditional institutions that are used to people of a certain age range and demographic attending.”

She hopes that the current situation will prompt us to do more in terms of pandemic preparedness, including “funding the NHS properly and funding scientific research properly”, saying that it’s highlighted the importance of “the general public having trust in their government and their scientific advisors so that we can go forward. A lot of the onus of that is on the scientists ... making out that science is very difficult and that you’re too stupid to understand it, so you should just take my word for it. That does not inspire confidence in the general public and I think we’re reaping some of the consequences of that now.”

Jacqueline has many ideas on how to stay engaged with science remotely, whether it be attending one of the many conferences that have moved online (she recommends the free Space Science in Context conference happening on May 14th, organised by her colleagues Divya Persaud and Ellie Armstrong), submitting your own “e-poster”, or doing a free online course. Lockdown hasn’t prevented Jacqueline from continuing her outreach work – the day before this interview, she gave a virtual talk about life on Mars to the children living on one of her colleagues’ street.

And on staying upbeat during a potentially isolating time? “I’d encourage people to join various forums and keep chatting to people. My mate does a quiz every week ... if you know anybody doing anything like that, join in online if you can to keep up your social life!”

The Schmidt Science Fellowship invests in “talented people who can make the world a better place, in the long run and even during some of the most challenging times in recent memory.” It’s no surprise that Jacqueline has been selected, as a perfect example both of a role model and a socially conscious scientist. She ended the interview by delivering “a big thanks to the University of Brighton where I did my undergrad, UCL, Mullard space science laboratory where I did my PhD, and the Schmidt Science Fellows for selecting me.”