Book Review: So Much Longing In So Little Space by Karl Ove Knausgaard

Bruno Reynell reviews the Norwegian writer’s study of his famous compatriot, Edvard Munch.

Two of Norwegian culture’s most powerful figures from present and past come together inSo Much Longing in So Little Space, writer Karl Ove Knausgaard’s exploration of painter Edvard Munch.

Yet, if you’re looking for a straightforward account of Munch’s life and work, this probably isn’t the book for you. While the book covers both of these things, Knausgaard adds other elements: art history, art theory and psychology, to name a few. The pages are also heavily imbued with personal memoir (would it really be Knausgaard if they weren’t?): at the beginning of the book he talks about Cabbage Field, a painting made by Munch in 1915. He describes the colours and shapes, of course, but he also explains what the painting means to him, how it makes him feel.

To focus so much on your own emotions in a book ostensibly about an artist might strike some as egotistical or at least a little self-centred. However, Knausgaard is not aiming to simply relay facts about Munch, this is a different book he is writing here, and his approach probably lends the book a smoother flow than it might otherwise have. More importantly, however, it allows him to ask questions about how individuals relate to art. Why do we like the images we like? Can our subjective opinion resist the opinions of others and the ephemeral artistic tastes of our time?

The focus on these questions is particularly acute when he writes on his experience of being asked to curate an exhibition for the Munch Museum in Oslo. His account brims with enthusiasm and excitement, but it is also plagued by anxiety and concern, as he fears his selection of paintings will be seen as ill-informed and amateurish. He is especially sensitive to the opinions of artists and academics – at one point he describes himself as hardly being able to get out of bed after a conversation with the artist Vanessa Baird, during which she criticised several pictures that he had (unbeknownst to her) selected for his exhibition.

While not always pleasant for Knausgaard himself, his interactions and interviews with other cultural figures do make for interesting reading. Amongst others, he talks to the artists Anselm Kiefer and Anna Bjerger, the art critic Stian Grøgaard, and the filmmakers Joachim and Emil Trier. They all tell him about their relationship to Munch, what they think of his works, and how their own work might relate to his. The answers are naturally diverse and emphasise how one painter’s images can hold so much sway within such a broad cultural sphere.

All this isn’t to say that we learn nothing of Munch himself. Knausgaard builds a picture of the artist through descriptions of his life and circumstances, as well as through speculation into the workings of his mind and how he related to ideas such as memory, time and place. Equally, Knausgaard explains the periods and changes in Munch’s painting, as well as how it related to contemporary artistic contexts. He isn’t the first great artist to have experienced personal tragedy and irreverence towards aesthetic convention on his way to creating iconic paintings, but there’s no doubt Munch led an intriguing life and career, and it’s all told in an accessible manner.

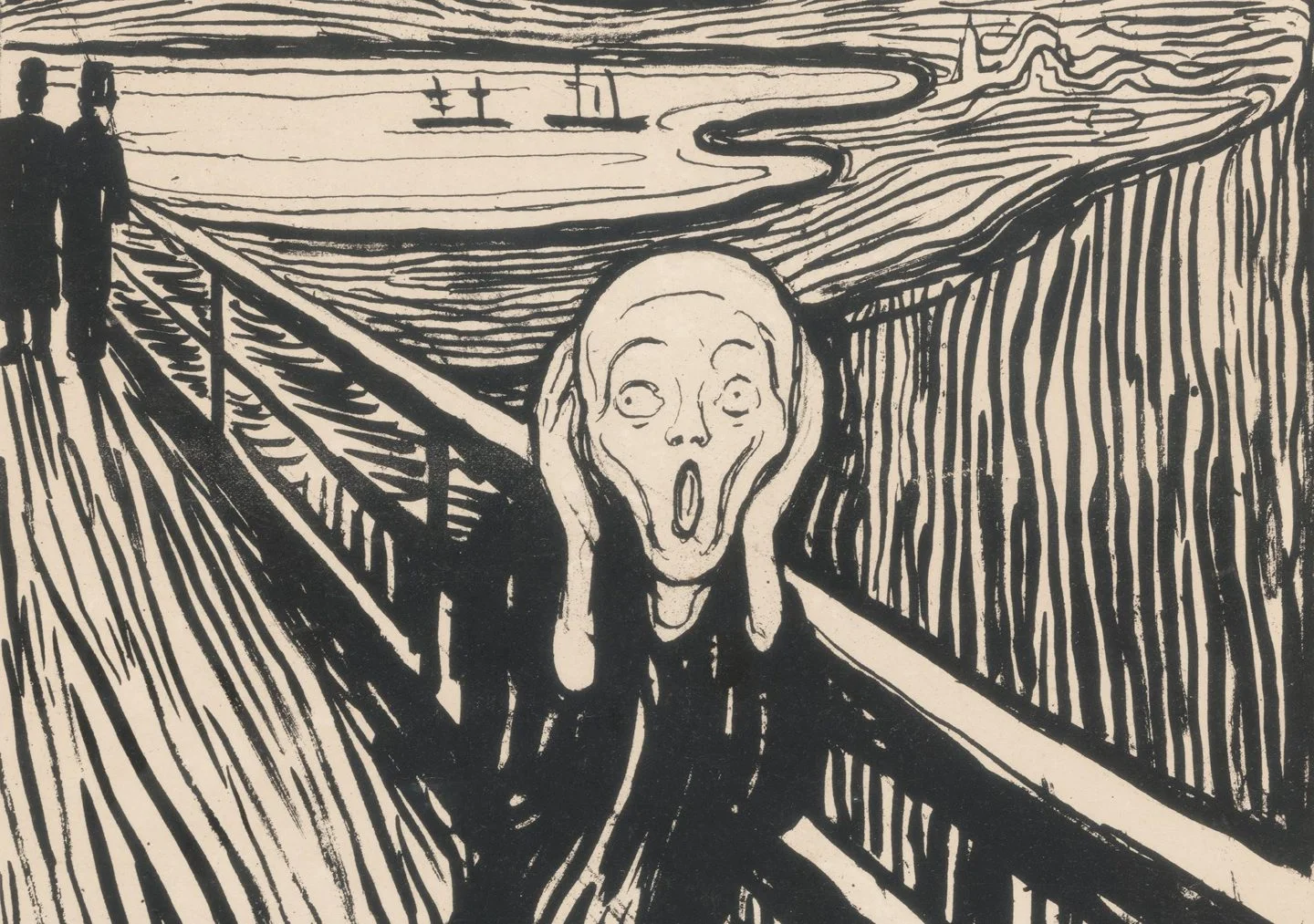

However, as Knausgaard acknowledges at the end of So Much Longing in So Little Space, there’s only so much the words of others can say about something visual. ‘Do I think this is great? Or do I just think it’s great because I’ve been told it’s great by other people.’ That’s what I remember thinking as I stood in front of a lithograph of The Scream, the headline piece at the British Museum’s current show on Munch. And perhaps it’s the most important message to draw from Knausgaard’s book – once you’re in the gallery, judgement should lie in the eye of the beholder, and the beholder alone.

So Much Longing in So Little Space by Karl Ove Knausgaard is published by Harvill Secker.