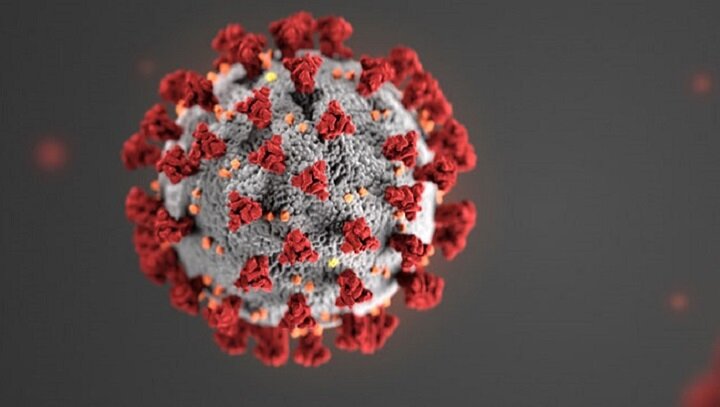

Coronavirus Series: What can we learn from Europe?

In the second of her installments on the COVID-19 pandemic, Tharania Ahillan evaluates the response of European nations and assesses what the UK can learn from them.

It’s safe to say that the coronavirus pandemic has been an unprecedented event. Markets are melting, life has been put on hold and the highest death rate has been reported since records began. Unprecedented events call for unprecedented responses.

In April 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO) outlined five global strategic objectives to combat coronavirus: mobilise all sectors, control cases and clusters, suppress community transmission, reduce mortality by providing the appropriate clinical care and develop safe and effective medicines and treatments. Countries are encouraged to adapt these strategies based on their risk, capacity and vulnerability.

Yet, the international community seem to have taken very different responses to the pandemic. At a time when cooperation amongst countries is key, it seems to have had the opposite effect, with countries blaming each other for the pandemic, and clambering over each other to claim access to valuable treatments, equipment and potential vaccines.

The Royal Society of Medicine’s COVID-19 series interviewed Professor Martin McKee, former president of the European Public Health Association, and Dr Natasha Azzopardi-Muscat, Director of the Division of Country Health Policies and Systems at the WHO, on their reactions to responses across Europe. They asked, how successful have these various measures been, and can the UK learn lessons from our geographic neighbours?

Germany

McKee and Azzopardi-Muscat highlighted Germany as a prime example of what to do. Germany boasts a low mortality rate with just 4.7% of those tested dying as of 12 June, (compared to 14.5% in Italy).

Professor Dame Anne Johnson, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at UCL pointed to Germany’s high testing rate as a reason for this number being so low when interviewed as part of the BBC World Service’s “More or Less” series. She explained that because Germany was testing more widely, milder cases were being identified and so the mortality rate appeared lower.

Still, it is evidence that Germany’s approach has benefited from a rich infrastructure in public health and testing in place already, with more than 85 laboratories present across the country.

It has certainly paid off politically. Merkel has inspired a great deal of public confidence and is doing well in the polls. She might have started off with the view that 70% of the German population would be infected with coronavirus, but the policies certainly aren’t reflective of this. In fact, Germany has always appeared to be confident that their health system can handle this crisis.

Bolstering the same kind of confidence here in the UK may be down to expanding our testing capacity as we move out of lockdown.

Sweden

Sweden has been unique amongst the Scandinavian countries with its comparatively relaxed measures. It has closed only its high schools and colleges, while primary schools, bars and restaurants are still open - as well as their borders.

Yet, one Swedish UCL student had reservations about its policy, “Sweden’s decision not to go for a lockdown approach was because they believed the healthcare system could cope, especially given the comparatively low population density and large proportion of single households. The majority of people here seem to approve of government policy, but I am worried about the large number of mortalities in care homes and low levels of immunity.”

This student’s fears appear to have been realised. Herd immunity in Sweden may not reduce the effect of a second wave. Sweden’s Public Health agency reported that just 7.3% of Stockholm residents had developed antibodies to the disease, not much different to general public rates of antibodies seen elsewhere of around 5%.

Given that death rates are much higher in Sweden than its Scandinavian neighbours, should the UK’s initial so-called “herd immunity” strategy be scrapped for good if we have a second wave?

Denmark

As the attention turns to reopening schools, Azopardi-Muscat says to look at Nordic countries which have already started doing the same with tentative success. The reopening of schools in Denmark seems to have been gradual, partly because parents were somewhat reluctant to return their child to school, but also due to the fact that, when measures were eased, a robust testing system was in place with relatively low levels of the virus in the country.

The danger in the UK is that the country does not yet have the testing response in place for children to return to school. In addition, the response is too centralised (so teachers, if they have a problem, will have to face a convoluted route to report it).

Azopardi-Muscat also raises the point that opening up the country too fast could lead to resources, which have been diverted to health, being diverted back and reducing capacity within the health system, with disastrous consequences.

Iresh Bhaskar, a former UCL Biochemical Engineering student, agrees and is “pessimistic that the government will regret easing the lockdown so soon.” Whatever the case is, the UK government will certainly be watching the situation in Denmark closely.

Italy

Italy may have suffered from high mortality rates, but one former UCL student from Pisa told Pi that Italy’s approach was still “miles better than the UK,” pointing to how effectively they have confined parts of the pandemic. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control supports her statement, reporting that much of Italy’s cases have been confined to the northern regions. In comparison, Azzopardi-Muscat explains that, here in the UK, we are seeing a much more general pandemic.

Comparisons are also being made within Italy of different approaches to identifying and treating diseases. Veneto, for example, has a good primary care structure, and appears to have been keeping people away from hospitals. In comparison, reports from Lombardy describe military trucks taking away corpses from the city of Bergamo. Strengthening the primary care structure, that is GPs, pharmacies and other services that are the first point of contact for many individuals, may be the factor that stops hospitals becoming COVID-19 carriers here in the UK.

Brexit

As the government decides to advance with Brexit during the pandemic, McKee cautions against this. “Not being in the same room where different ideas are being discussed has already hampered its response… an approach with greater integration to the rest of the continent is key in moving forward.” He suggests instead the UK government should be putting the brakes on Brexit for now. Indeed, one UCL student remarked on UCLove that they loved that “everyone’s forgotten about Brexit now that [COVID-19] is in Britain.”

There are certain caveats to comparing at this stage though. While comparisons can be made on a large scale, it’s difficult earlier on if numbers are similar, like they are for mortality rates. Public health experts are instead much more interested in using multiple indicators for a more accurate comparison.

It’s also clear that viruses don’t know borders, which begs the question: should we be comparing countries or instead looking at class and socioeconomic factors?

Still, it’s clear that comparing strategies and learning from other countries ahead on the curve will be key to restarting economies without undoing all the hard work put in by various measures, and transitioning out of this pandemic.