I, Joan – The Future of Theatre?

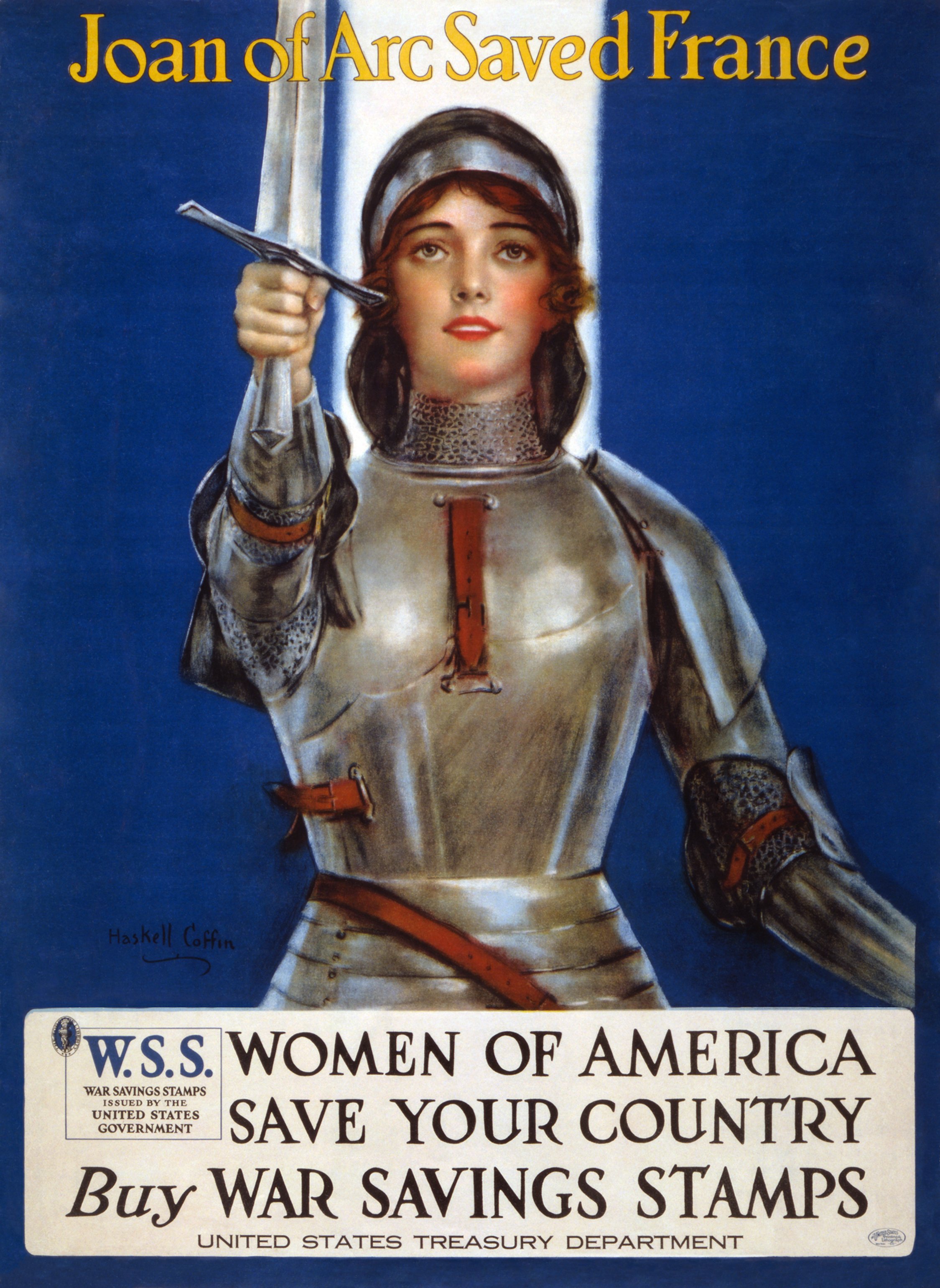

Picture Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Disclaimer: This article refers to both the historical figure Joan of Arc and the character Joan from the stage production as “them” for the sake of continuity and respecting the author’s focus on the theatrical production.

I, Joan, tells the life story of Joan of Arc, a French peasant-turned-warrior who fought in the Hundred Year’s War, but who was eventually burned at the stake. The play, written by Charlie Josephine and directed by Illinica Radulian, premiered earlier this summer at Shakespeare’s Globe. Although not the first theatrical production to tell Joan's story, I, Joan reinvents the historical character with a refreshing complexity.

In Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part One, Joan is perceived as a ‘sweet virgin’ by the French, but a ‘witch’ by the English. Joan’s multifaceted character continues to place them as the muse for many artists and the interest of discussions six centuries after their death.

In 1936, Vita Sackville-West opened the discussion on Joan’s sexuality in her biography Saint Joan of Arc. Although some evidence in her work was criticised as lacking, the fact that Joan preferred to wear traditionally male clothes and refused to conform to medieval expectations for women marked them not only as feminist, but as the ‘essence of transgressive androgyny’.

Josephine continues to invest in Joan’s identity by reimagining them as non-binary. The play starts with a prologue where Joan (Isobel Thom) asserts that ‘transpeople are sacred’. Beginning on such a powerful note, the play then moves on to offering the audience with witty remarks, funny absurdity, and emotional resonance.

With the playful stage design, the actors constantly and comically slide down from and climb up to the musician gallery. Alongside colourfully dressed soldiers in Joan’s army, the stage is as dynamic as a party. Just as Josephine hoped the play to be: — ‘fizzy and sweaty and working class and queer and questioning and searching’ — the Globe’s groundling yard turned into a dance floor under London’s late-summer sapphire sky with the audience marching along with Joan.

Despite the raving applause heard at every performance, I, Joan faced backlash even before its opening — the most prominent criticism being the lack of historical accuracy of the show since Joan is presented as non-binary. The lead actor, Isobel Thom, even tweeted that ‘nobody is taking away your joan’. Nevertheless, the seemingly presumptuous comments have posed a question to modern-day theatre: is it free to diverge from the historically accurate depiction of its characters?

This seemingly difficult question, however, can be answered rather easily. If one traces back history, they will find that even Shakespeare did not write historically accurate plays. It is not hard to tell that theatre has never been built strictly on historical facts. And it should never be. Theatre, like any other form of art, offers a place of imagination – it is a place where ‘for a brief amount of time, we can at least consider the possibility of world’s elsewhere’. The fact that people denied a character different from their own version, without even caring to see how it is portrayed, seems rather dogmatic.

Like Joan says in the prologue, I, Joan is a ‘celebration’ and a ‘revolution’. Not only does it celebrate non-binary identity, but it also shows the vastness, boundlessness, and richness of theatre. I am certainly looking forward to seeing more productions like I, Joan, and more characters like Joan.