Mental health in retrospect

Rebecca Daly and Matthew Bazley discuss the shift in our understanding and treatment of mental illness.

In the summer of 2019, UCL founded its own Institute of Mental Health. Shortly after, the NHS launched the ‘Every Mind Matters’ campaign. Though it may seem like a recent phenomenon, the history of mental health traces back to the earliest civilisations, often featuring the stark mistreatment and misunderstanding of patients. Fortunately, as our awareness of mental health has increased, significant progress has been made in understanding and treating it. However, there is a considerable way to go.

Mental illnesses were historically attributed to physiological problems and treated accordingly. Indeed, one of the earliest forms of surgery, ‘trepanation’ — a procedure in which a hole is made in the skull of a living person — is theorised to have been an ancient treatment for mental illnesses, at that time credited to evil spirits. Mesopotamian and Egyptian papyri detail what was later termed ‘hysteria’ by the Greeks: a mental illness caused by a ‘wandering womb’ preventing normal organ function. This was treated through use of attractive pleasant smells, and repulsive unpleasant ones to relocate the womb to the correct position. Prominent Greek physician, Hippocrates, attributed mental disorders to an imbalance in the four humours in the body: yellow bile, black bile, blood, and phlegm, corrected through bloodletting and purging. This theory remained part of mainstream science up until the 19th century, and was undoubtedly a stepping stone towards our current understanding of mental health.

By the 13th century, mentally ill people had begun to be persecuted as witches: they were forced to confess, then brutally punished through hanging or burning. Dutch physician, Johann Weyer, was one of the first to publish works against the persecution of witches in his 1563 book ‘De Praestigiis Daemonum.’ It is said to have been the first to use the term ‘mentally ill’ when describing those accused of witchcraft. 21st century physicians have now matched the symptoms shown by these ‘witches’ to neurological disorders, such as hysteria and epilepsy.

This widespread stigma informed the violent treatment of the mentally ill during the Middle Ages. Aiming to isolate those affected from the rest of society, this period saw a shift in responsibility of care from families to the newly built asylums. London’s Bethlem asylum, better known as Bedlam, was one of the first, founded in 1247. Brutal ‘treatments’ were inflicted on patients, including hydrotherapy and the employment of mechanical restraints, such as straight jackets and manacles. As popularity increased and asylums filled up, these were techniquess intended to control rather than to treat. Such asylums were common up until the turn of the 19th century, when George III’s ‘insanity’ increased interest in mental illness. UCL itself played a large role in revolutionising the treatment of the mentally ill at this time: the Professor of Psychiatry, John Conolly, was instrumental in overturning the use of mechanical restraints in 1830. Later in the 19th century, Acts of Parliament were passed to improve conditions in asylums.

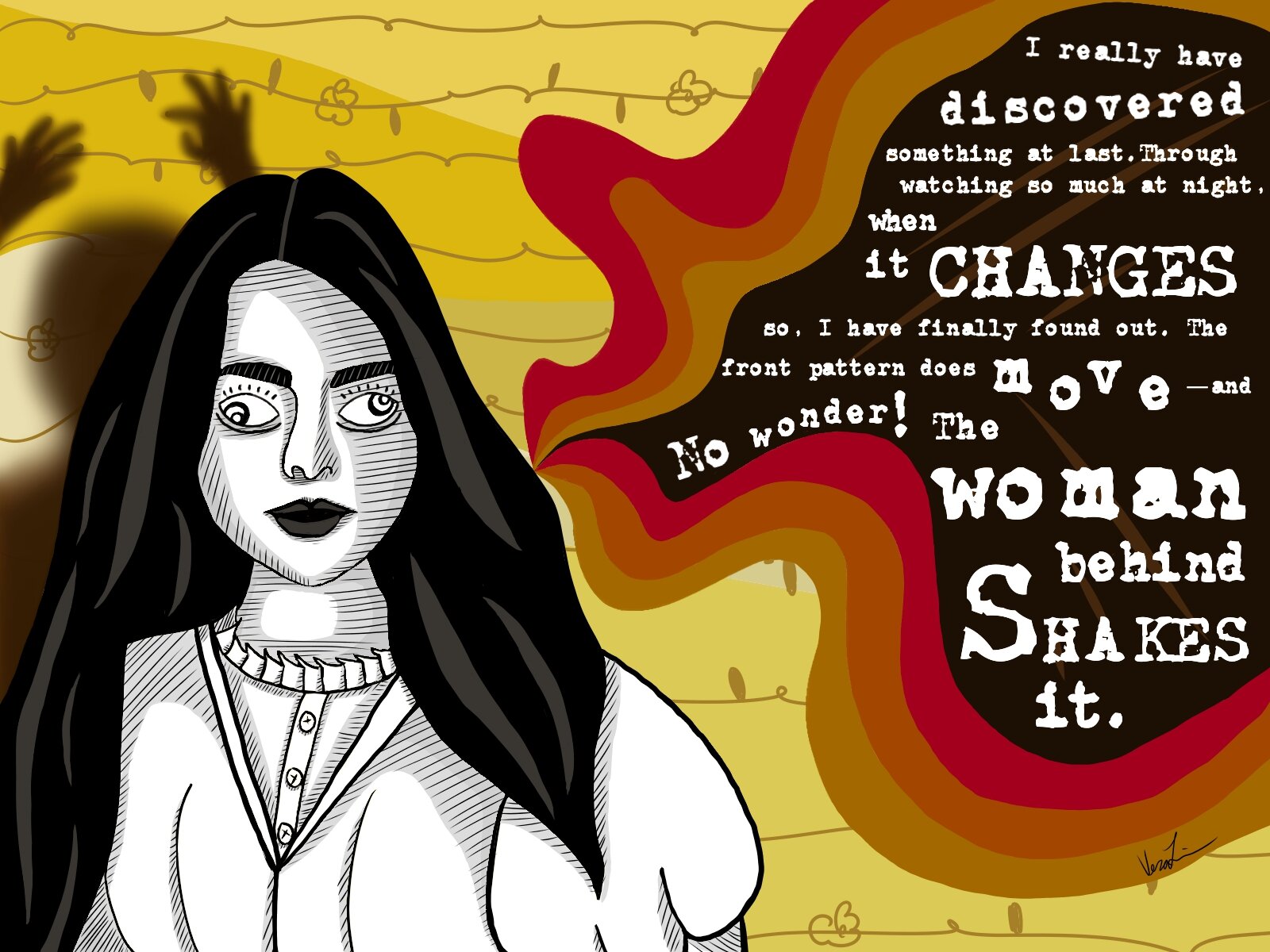

In the late 19th and early 20th century, physicians began to abandon the somatic view of mental illness due to increasing awareness of the psychology behind it. 20th century neurologist Sigmund Freud founded psychoanalysis, of which the core idea is that of the unconscious. Josef Breuer, Freud’s mentor, shapedthese pivotal ideas through the introduction of ‘talking therapy.’ Through therapy, Breuer and Freud were able to match up stories and dreams told by Anna O, Breuer’s patient, with her physical symptoms, aiming to bring unconscious trauma into consciousness. Her gradual recovery marked a turning point in the understanding and treatment of mental illness, laying the foundation for Freud’s later theories. One such idea was that repressed trauma from childhood events is manifested as neuroses, buried in the unconscious mind. The treatment was to therefore make some of the unconscious conscious, so that a solution could be found. His techniques greatly influenced the development of modern forms of therapy, such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), which aims to help the patient understand their thought patterns. Though Freud’s ideas are controversial to many, there is no question that he shone a spotlight on mental health issues. The effects of this surge of interest in psychology was notable too at UCL, which became one of the first English universities to set up a psychological laboratory. In 1901, the British Psychological Society was founded.

Despite these leaps forwards, one form of particularly controversial treatment reached peak popularity during the 1940s and 1950s: electroshock therapy. This stemmed from the idea that certain disorders were antagonistic to epilepsy, and thus could be cured by the induction of seizures. Electroshock therapy frequently resulted in memory loss and brain damage, rarely yielding significant improvements in condition. This was prescribed overwhelmingly to women and vulnerable people, often without their consent. Following vilification in popular media, the treatment has been refined to electroconvulsive therapy, which is still— controversially— administered today.

In 1951, a new drug for tuberculosis called Isoniazid was given to patients in New York. Unexpectedly, there was a shift in the mood on the ward, from gloomy to cheerful. Only three years later, a patient with high blood pressure was prescribed Reserpine, leading to equally astounding lethargy and depression. This trend continued nationally, with suicidal patients being administered ECT to alleviate the terrible symptoms caused by the drug. These events were to change psychiatry forever. By the 1960s, scientists had discovered neurotransmitters, chemicals that carry signals between neurons. It was found that Isoniazid, the drug that improved the mood of patients, increased levels of the neurotransmitter, serotonin, while Reserpine did the opposite.

This discovery led to the development of the chemical imbalance theory,’ proposing that depression was due to a lack of serotonin in the brain. A new class of serotonin enhancing drugs called Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) was created. The first and most famous of these drugs was Prozac, developed in 1974 and released some 10 years later. Drugs like Paxil and Zoloft were approved in the following decade, primarily to treat depression, anxiety, OCD, and PTSD. Practically all the drugs for mental illness used today work by regulating neurotransmitter levels. Similarities between the chemical imbalance theory and the humorism of the Ancient Greeks are certainly telling. But since then, advances in neuroscience have provided new outlets to explore.

The picture of mental illness is far more complex than we once thought. Since the 1970s, experiments testing the chemical imbalance theory have been consistently unreliable in showing a correlation between neurotransmitter levels and various forms of mental illness. In the 1980s, neuroplasticity, the idea that the brain is a constantly changing structure, revolutionised neuroscience and provided a new avenue for research. It has been proposed that SSRIs are so effective because they can improve neuroplasticity, possibly by increasing levels of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a chemical promoting the production of neurons in the brain.

Though there has been a vast improvement on historical practices, there is some concern that these drugs have become overused, with a simple prescription being an easy way to fix a complex problem. It’s clear that mental health issues can arise from emotionally stressful situations. Other approaches to treatment, such as counselling and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, are emphasised as being equally important.

Despite this progress, there is still a long way to go in terms of removing the stigma around treating and talking about mental health. Research has also shown clear but complex intersectional racial and gender differences in the risk of developing mental health problems, and the likelihood of seeking and receiving treatment. Institutions such as UCL have a responsibility to provide better support to its students, who are often placed under immense psychological stress from all areas of life.

If you’d like to talk to someone in confidence about your mental health, UCL’s Student Support and Wellbeing team offer counselling sessions. Alternatively, there are many online services, including the Samaritans, NHS Choices’ Moodzone, and Students Against Depression.

This article was originally published in Issue 724 of Pi Magazine.