What makes good art - and who gets to decide?

Matilda Singer responds to Rebecca Watt’s scathing criticism of ‘popular’ poetry.

Last month, poet Rebecca Watts wrote a scathing review of fellow poet Hollie McNish’s latest collection Plum in PN Review. Titled The Cult of the Noble Amateur, Watts’ review served up intellectual criticism, her comments sparking a huge debate in the literary world – a debate about what exactly makes someone a good poet. A debate that I feel I must weigh in on as both a reader and a writer of poetry.

Let me start by saying that Watts is well within her rights to critique McNish’s work. I may not agree with it because, personally, I like Hollie’s poems. Many are expertly crafted, quite frequently they are funny and the subject of her work almost always means something to me – but I understand why someone might not get on with her poetry, just as I don’t enjoy other celebrated writers. However, what I find fault with is the nature of Watt’s criticism: the fact that her complaints are not about the work, but rather about McNish as a person and her route to success. In the review, Watts lumps together McNish, musician and spoken word poet Kate Tempest and Instagram poet Rupi Kaur and makes a grandiose complaint about where the world of poetry is heading. That is, that poetry is being dumbed down thanks to the ‘rise of a cohort of young female poets’. In her closing statement Watts urges us to ‘stop celebrating amateurism and ignorance in our poetry’. Not only is this a patronising and supercilious argument, but conflating these three very different poets is an insulting misrepresentation of their work. McNish and Tempest’s collections contain a number of short simple poems, but this is not their defining feature (in fact, Tempest’s epic poem Brand New Ancients is 47 pages long).

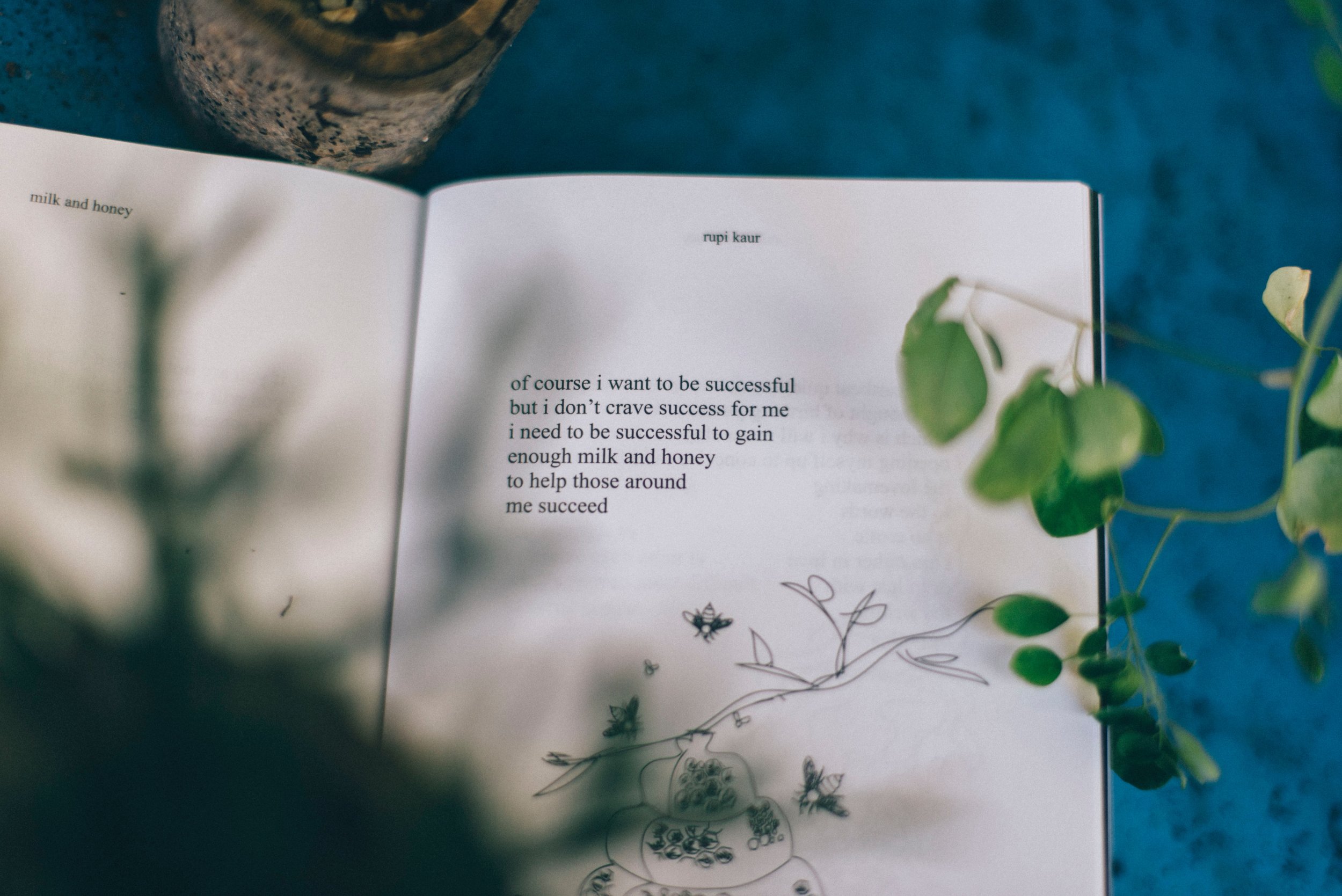

Comparatively, Kaur is famous for her distinctively short poems. She began uploading these to Instagram a few years ago, quickly gaining attention (and a large following) thanks to the relatable and easily digestible content. Her popularity caught the attention of publishers and her first collection Milk and Honey has now sold over a million copies, a rare feat almost unheard of in the poetry world. Many would argue that Kaur is pushing the boundaries of what counts as poetry, which I would hesitantly agree with. (I admittedly find myself chuckling at the numerous parodies of her work that can be found on Twitter.) However that doesn’t mean that her writing isn’t good or that it doesn’t mean something to her readers. I think what many literary critics dislike about Kaur is that she is extremely popular. Watts confirms this when she argues that ‘the ability to draw a crowd…does not itself render a thing intrinsically good’. While this is true, it also works both ways meaning that a large following doesn’t necessarily indicate lazy poetry either.

What also makes these poetic styles so easy to criticise is their simplicity. Of course there is something deeply rewarding in spending time and energy unpicking an obscure poem. Analysing literary techniques and researching the context surrounding the poet certainly gives you a greater depth of understanding. It’s a gratifying process, in many ways more so than reading a three line poem and immediately ‘getting it’. But what is wrong with the greater accessibility of poets like Kaur, McNish and Tempest? Poetry is notoriously unpopular with the general public, selling less copies and being less discussed than novels or short stories. Many readers are put off engaging with poetry whilst at at school, forever feeling they are not qualified enough or smart enough to understand the work. If these writers are opening up poetry to the general public and acting as a gateway to other collections, then surely we should be celebrating them?

When I first read the article, I wanted to argue that Watts can’t compare McNish and Tempest to Kaur because the former two are published by Picador and have won Ted Hughes Poetry Awards. I even had to stop myself saying that there can be no comparison because they are ‘proper’ poets – because what is a ‘proper’ poet? Surely you can call yourself a poet if you sit down and write a few lines of verse every so often? Fencing in poetry as one particular way of writing makes it a secretive art. An elitist way of keeping literature safe within the halls of academia. For me, this is the most tragic thing about such an argument. Literature, indeed any form of artwork, should be shared around for everyone to enjoy, regardless of their training or background. Watts apparently disagrees. She explains that ‘in other contexts, elitism is not considered evil’ and makes a ridiculous comparison between training to be a surgeon and developing your skills as a writer.

At the end of the day, this debate raises huge unanswerable questions. What is art? What qualifies as good art? And who gets to decide? In academic terms, a good poem could mean verse constructed with advanced literary techniques, but it could also mean a poem that has some deep personal meaning for readers. McNish was brave enough to respond to the article on her blog with a witty rebuttal, rightly pointing out that the review ‘goes further than any writing critique to make assumptions about my (lack of) education, my love (or not) of language and my personality’. While Watts may be attempting to make some valid points, she is heavy handed with hyperbole and far too personal in her attack, which leaves the entire piece smelling suspiciously of literary snobbery. Poet Lemn Sissay captures my response perfectly when he reminds us: ‘There’s room for all forms of poetry. And whichever side you’re on, it’s foolish to say there isn’t.’