A Fiction Boom: Why Escapism is Selling Out

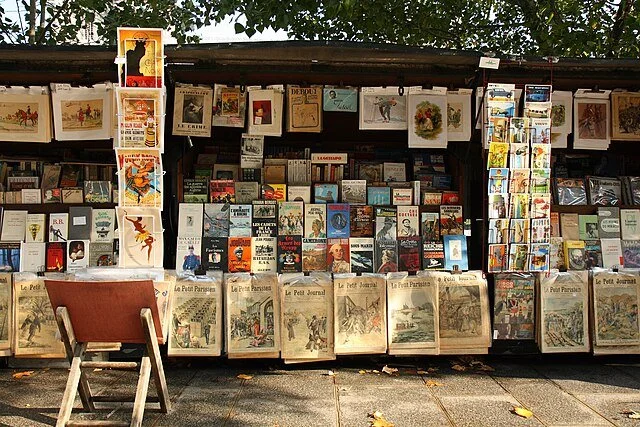

Image credit: Ben Lieu Song via Wikimedia

The self-help shelf will always hold court by the front door of a Waterstones, beckoning the passing commuter with promises to regulate dopamine levels, manage money, or tame the very anxiety such quests for self-improvement provoke in the first place. However, as an avid reader first and English Literature graduate second, my last three years navigating the sprawling selection at Gower Street’s landmark bookshop has made me realise that readers are slowly drifting away from didactic memoirs and manifestos towards fiction.

Perhaps my professor’s austere exclamation to ‘stop reading self-help books, just read Montaigne!’ is finally starting to take hold of the average reader.

Where, in my first year as a fresh-faced undergraduate, I had to feign interest over endless discussions about Prince Harry’s rather uninspired memoir, I now see authors like Joan Didion and Sally Rooney stacked at the top of the piles that customers carry toward the till – blessed be their paperbacks.

For much of the 2010s and early 2020s, nonfiction reigned supreme, with the bestsellers table amassed with blueprints for how to survive the world we currently live in. Its long reigning monarch, one of the first books you see upon entering Waterstones, is Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. The book surveys the history of humanity, from the stone age up until the 21st century. The success of such a book indicates how reading, turning away from the joyful periodicals of the Victorians and experimental poetry of the 60s, became a tool for survival; an attempt to decode a world that was coming apart at the seams. We devoured memoirs and guides with the same desperation we once reserved for fiction. How Democracies Die, how Atomic Habits form, leisure consistently had to prove itself productive.

In hindsight, the 2010s was a decade obsessed with explanation. Following the 2008 financial crisis, the election of Donald Trump, Brexit and finally, the pandemic. The sequence of shocks and ripples consistently stripped life of certainty and stability.

Readers subsequently turned to information as a form of control. The more the world spun out of hand, the more we tried to index and understand it. There was comfort in a voice that claimed to know. Perhaps humanity’s desire for an ‘all knowing’ authority was simply a way to cope with increasing secularisation. The promise of omniscience repackaged into TED Talks, Substacks and Barack Obama’s memoir. Perhaps the human condition is simply too unbearable without someone pretending to know how it all works.

To borrow from the French philosopher, Jean Baudrillard, we are now living in the age of the hyperreal. A world so saturated with information that its meaning has started to dissolve. Everyday, millions of posts rush through the same narrow channels of our attention. Simultaneously, social media ensures that every event, both tragedy and joy, arrives digested and captioned. Interpretation becomes something that we are fed and that we consume rather than one we perform ourselves.

Think of the unprecedentedly commercialised death of Christian Nationalist, Charlie Kirk, whose assassination prompted his widow Erika Kirk to post a video of her perfectly manicured hands holding onto his now cold ones. A moment of mourning turned into a performance of authenticity. When the most elemental and visceral of human experiences - grief - arrives indistinguishable from a performance, a fundamental part of our humanity tires. Fiction therefore, begins to feel increasingly grounding when the real world increasingly resembles a performance – precisely because it is the one form of media that isn't vying for authenticity and admits outright its falsity.

It’s therefore no mystery why readers are finding their way back to the old pleasure palace of the novel. After a decade spent clawing for clarity in works of non-fiction, when a book admits upfront that it is false to you, the mind can finally loosen. You’re no longer being asked to sift signals from noise or parse ‘authenticity’ from performance. Rather one is allowed to follow a fictional consciousness untethered from the exhausting demands of real life. Within that suspension lies relief.

So perhaps my professor’s potentially cerebral advice was not about his undying love for Montaigne after all (though highly unlikely). Rather it was about returning to literature and fiction as a kind of unlearning. An invitation to stop seeking meaning and start noticing again. That in suspending the search for truth, we sometimes find life.