The Tragedy of Colonialism: Medea at the Bloomsbury Theatre

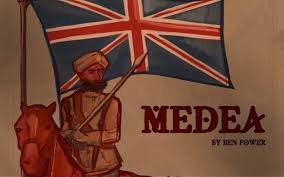

Image Credit: UCL Drama Society via UCL News

Last month, I had the privilege of viewing the UCL Drama Society’s reimagining of Medea. One of the more unsettling Athenian tragedies (and it has Oedipus to go up against!), Euripides’ play must have been a great undertaking to stage. But of course, Medea should be staged today! It is a tale of broken oaths, of collective, familial, and individual obligations, all locked in a life-and-death struggle against one another; it is a tale that asks: who gets to tell whose story?

Today, we are in many ways overly familiar with these concerns so much so that modern readers and audiences always find themselves astonished by the ‘modernity’ of such ancient texts. More specifically, these are concerns of an age in which European colonialism is a living yet contested memory. It seemed like a natural choice, then, for director Aria Singh-Bernath to situate the play in Rajasthan in 1853. Jason’s abandonment of Medea in favour of Kreon’s daughter dramatises in broad strokes the real process by which indigenous rulers were integrated into the colonial regime. The names of characters and gods remain the same as in Euripides’ text, but changes in place names accompany a complete visual overhaul, transporting the audience to the subcontinent.

A spatial opposition is added alongside those listed above. The stage is split vertically: below, a landscape of dull brick, on one side the Union Jack is planted like a symbol of a victory long since achieved; above, a platform decorated with ornate cream wallpaper. The visual unevenness is matched by aural dissonance. Nearing the climax, we hear the drones of an Indian raga (performed live) interrupted by the grand melodies of Western orchestral music. Such is the palimpsestic texture of colonialism.

All of this was accompanied by a series of terrific performances. Isabelle Flynn seems to have had the entire emotional spectrum at her fingertips as the play’s eponymous heroine; I was equally impressed by the chorus, whose lines were expertly split up so as to make each member a unique character in their own rights. Aristian Karanikolas’ take on Kreon was by far the standout performance. In his interactions with Medea, his whole being became the battleground of sympathy and sternness, bringing out a humane quality to the character that might not have been so evident in Euripides.

There are, however, concerns of a historical nature. The play is set in Jaipur, with Kreon taking on the aspect of the city’s British governor. It is a potent visual, resonant with popular conceptions of colonialism. At this time, however, Jaipur was governed internally by its own Maharajas; its relationship to the British Empire was one of tribute, not direct rule. Historical accuracy should not be the primary metric for evaluating a work of art, but surely this sort of confusion could have been avoided if they had chosen, say, Bombay or Madras instead?

Regardless, the UCL Drama Society delivered a thoroughly engaging take on so gruesome a play. The spirit of Attic tragedy is certainly felt in the two piercing screams that occur during it, extracting both pity and fear from the audience so efficiently that you’d have to call it some kind of fracking.

I hear that yet another production of Medea is in the works at the Cambridge ADC. Though the Venn diagram of people who will have seen either production – ours and theirs – will likely only have my name in the centre, I am nonetheless eager to see what direction they take it in. They’ve certainly got fierce competition.