Blood and Bias: The Journey of Menstrual Product Design

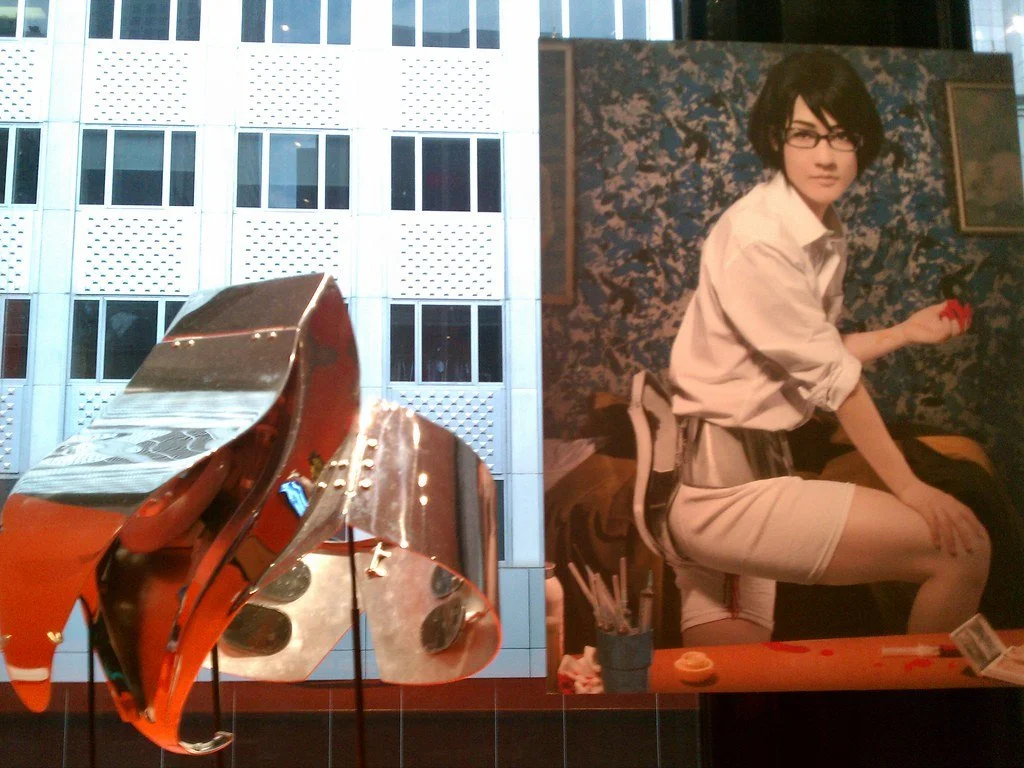

Image Credit: "Menstruation Machine, by Sputniko!" via Creative Commons

“Ugh, great. I’m a week early. Got a spare square of papyrus?”

…Is maybe not exactly how the conversation would have flown in ancient Egypt.

In fact, any dialogue surrounding periods, even today, is a rarity. But it is true that before our modern age of tampons, pads, menstrual cups, discs, period pants, (some cheeky toilet paper, or, for the bravest amongst us, nothing at all) period products used to be largely organic. And according to National Geographic, softened papyrus is ‘the oldest record of period management’.

People in the past may well have used anything available: moss, old cloth, purposeful layering of skirts, and so on. Deterioration of these biodegradable products over time, as well as stigma surrounding the very topic of menstruation has made it difficult for archaeologists and anthropologists to create a clear picture of the day-to-day methods of the historical menstruator.

In an era of Tampax and Always, it seems as though product design has developed from literal rags to riches. And yet there are still issues surrounding product distribution and safety. A report published earlier this year by Pesticide Action Network (PAN) found a popular brand of tampons in the UK contained glyphosate in levels 40x higher than what is permitted in drinking water. Glyphosate is a herbicide that has been labelled a probable carcinogen, facing strict regulated in the UK.

The report also stresses that the ‘absorption of chemicals through the vulva bypass metabolism and enter directly into blood circulation.’ Determination of ‘safe’ toxicity levels of glyphosate only consider exposure through the mouth, i.e. ingestion, which is an inadequate, inappropriate framework for testing the levels in menstrual products.

Additionally, disposable pads and tampons pose an undeniable threat to the environment, with the UK using 3.3 billion units of single-use products annually. A sanitary pad or a tampon is familiar, ever-present, unavoidable. But what if there was something better?

Research suggests that collaborative, interactive workshops are crucial in generating new designs. In the study, menstruating individuals were sampled as participants and paired together based on the closeness of their relationships, creating a comfortable, non-judgemental space to stimulate innovation. Despite minimal resources, this environment yielded productive evaluations on the usefulness of a range of products, and individuals were able to begin working on more effective, inclusive prototypes. Overall, centring the experiences of menstruating individuals is essential in product design; active measures must be taken to reject any stigmatised attitudes during research.

PAN’s report has yielded little systematic change in the UK government’s (lack of) regulation on distribution and labelling of period products. Disposable products, after polluting our bodies first, continue to end up in landfills. In light of PAN’s publication, and as UCL ranks 1st in the UK for sustainability, perhaps it is time for us to consider more carefully the health concerns and environmental implications of single-use period supplies, as well as support studies on new methods of innovation in the industry of menstrual products.