Exhibition Review: David Hockney at Tate Britain

DOES THIS RETROSPECTIVE DO JUSTICE TO ONE OF BRITAIN’S FAVOURITE ARTISTS?

Last year, David Hockney brought a new series to the Royal Academy – a collection of eighty-two equally sized portraits of different sitters, each in identical surroundings with only their individual features and character to distinguish between them. Other recent exhibitions have included the Yosemite Suite, comprising of a number of paintings and iPad drawings of the national park featuring the same bright palate as those of his Yorkshire landscapes. Hockney has had a fair few exhibitions in recent years, although seldom a full retrospective – the last was in 1988. Tate Britain’s current retrospective of David Hockney has been long awaited in justified anticipation and garnered record levels of interest, and yet the display is not without its difficulties.

This is a full chronological inspection of the artist’s oeuvre, hotly anticipated to be a once in a lifetime showing. Introduced with the brilliant ‘Play within a Play’ room, six works from a number of decades are brought together to display the witty reflexivity of Hockney’s medium. Any seasoned Hockney viewer must be familiar with this artist’s references to photography, and indeed to the art historical canon. It is a delight to trace Hockney’s stylistic and subject choice to the twentieth century avant-gardes as well as the English printmakers of the eighteenth century – seen in the pleasing ‘Kerby (After Hogarth) Useful Knowledge’. This room stitches together illusionistic works, offset by aspects of realism, and works that move away from single-point perspective, introducing the other aspects of Hockney that the unassuming L.A. scenes do not express.

It is a stretch to call this room emblematic, or even a decisive marker of what is to come, and it is by no means an extended theme of the retrospective. Perhaps to the exhibition’s detriment, the selection of artworks pushes towards a continuity in Hockney’s work that is less clear than it likes to think. Each room marks a decisive shift from the last, with the bold use of colours returning in later works, yet with a vastly different intent and subject to them.

The 1963 painting ‘Play Within a Play’ takes from a photograph of Hockney’s friend John Kasmin, in a humorous play with illusion and the photographic medium. The subject presses his flattened body against the panel of perspex that separates him from the viewer, his hands imprinted in true effect against the glass in rapt anticipation. The painting shares the intimacy with his subject matter with his L.A. scenes and Yorkshire landscapes, but somewhat lacking in the clinical glare of the iPad sketches. The paintings from Hockney’s time at the Royal College of Art hold a considerable allegiance to the pop movement, yet the exhibition’s choice of artworks offer a conflicted selection that displays experimentation without the clear intent that marks out the later works. Hockney’s play with photographic conventions is known to those familiar with him – ‘A Bigger Splash’ (1967) and ‘Peter Getting out of Nick’s Pool’ (1966) are among the popular selection of Hockney’s sixties works.

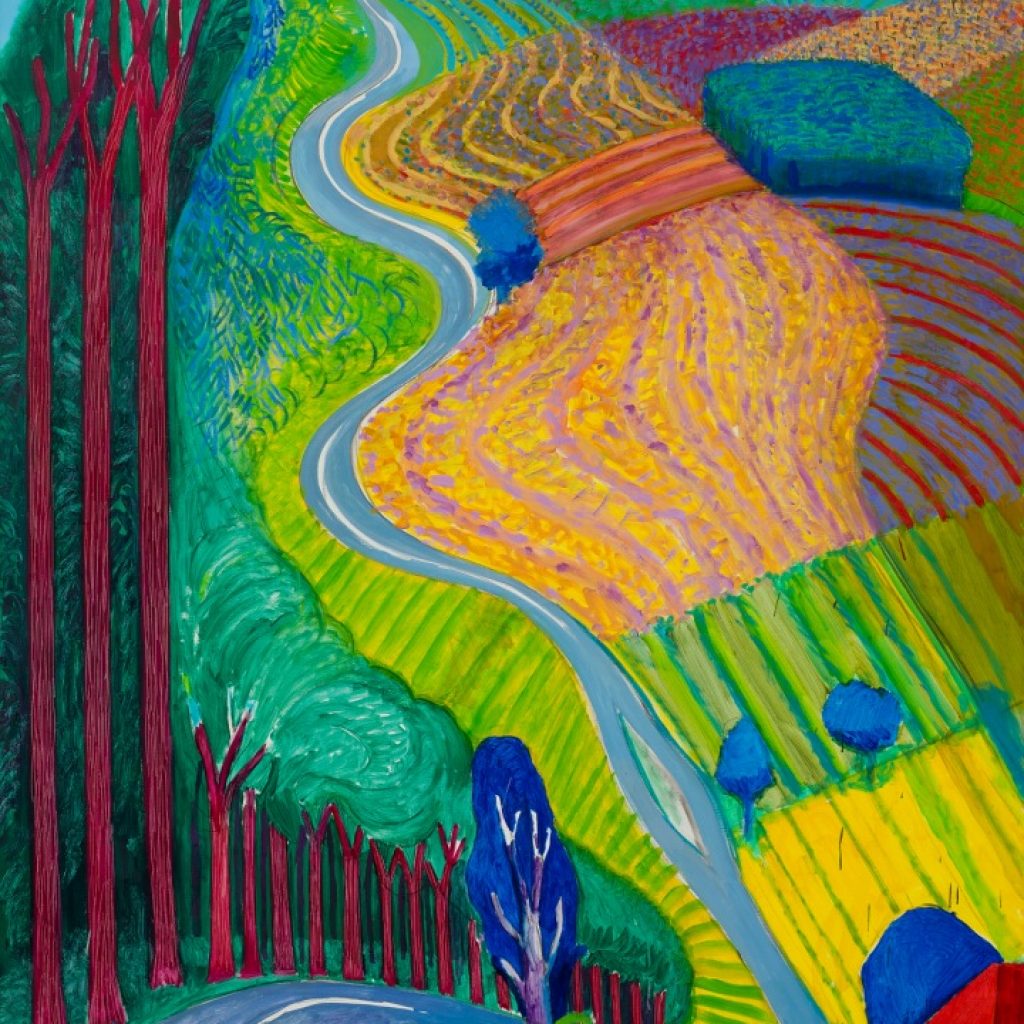

The following rooms display the wide breadth of Hockney’s later works, with his turn to the natural landscape of Yorkshire, California and the Grand canyon. ‘The Four Seasons’ (2010) has been derided as laboured and stilted by its critics, but this is highly undeserved. These multi-screen video works display the Yorkshire landscape of Woldgate in true cubist fashion, with each monitor showing a different perspective as the view pans along the road. Each three-by-three grid shows a different season, with each wall of the gallery bringing alive the technique of the polaroid works of the ‘80s and ‘90s, stitched together to create a jolted perspective of the subject. Herein, Hockney enlivens the photographs with a video accompaniment.

It’s an unfortunate consequence of the chronological layout that many will find reason to place the 1960s works as the best that Hockney has to offer us. Perhaps, unfairly, the retrospective suffers from fatigue by the later rooms. With the display certainly peaking halfway through, and waning from then on, a more careful selection of Hockney’s work could have done a lot more with fewer works. Whether Hockney’s later work reflects a subduing of the artist’s exploits in his later years, I am not convinced. Indeed, the use of new technology to produce art has certainly been fruitful to aligning with Hockney’s familiarly bright palate – aspiring draughtsmen or amateur sketchers are sure to benefit from this display of iPad drawings-in-progress.

However, this is the Hockney that the nation loves and rightly flocks to. The collection of works on show is without match, and certainly something special to visit as a once in a lifetime showing of all of his work. The variety is bound to bring you to a new side of Hockney, previously unexplored.