God’s Creatures Review: Solid Gothic Drama That Rarely Probes Beneath the Surface

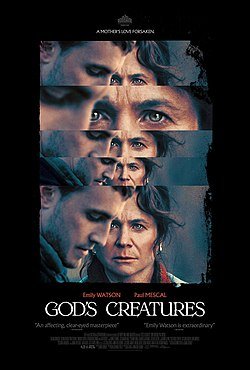

God’s Creatures theatrical release poster

The strengths and weaknesses of God’s Creatures come from its implacability. Its plot is very simple: a story about a mother protecting her son for a crime he almost certainly committed. When Brian O’Hara (Paul Mescal) returns home unexpectedly, his mother Aileen (Emily Watson) is delighted. But, when the police call round one night concerning an allegation of sexual assault against her son, she instantly provides him with an alibi. It is through this struggle with guilt and trauma that a remote Irish village’s traditions fall apart; their patriarchs self-destruct, and prove themselves, and their way of life, to be unsustainable.

It must be noted that if you come to God’s Creatures looking for any overt discussion of this dilemma, you’d be disappointed. Instead, you get a demonstration. The eerie soundtrack, sublime shots of the landscape, and a rhythm that spirals from monotony to nightmare, creates a tone closer to horror than to pure drama. In that same vein, anyone coming to God’s Creatures expecting a drama may be disappointed. The unsustainability of the village’s economic and ethical approaches inevitably leads to their own destruction. It’s an unsettling journey, and gives the audience plenty of space to contemplate and project their own experiences onto the film.

The performances are all measured and well-executed; Emily Watson as the mother and Lalor Ruddy as the geriatric grandfather are note-perfect in their roles, however the characters themselves are too formal to be seriously excited by. The most obvious reason for people coming to watch this admittedly generic indie slow-burn, with a mixture of social justice and representation for usually ignored communities, is the presence of Paul Mescal.

It's his first wide-release film post-Aftersun and his turn as Stanley in A Streetcar Named Desire on the West End. The allure of Paul Mescal in this day and age is that he’s just some guy, and that’s a novelty. Beyond that, we haven’t been oversaturated by him across dozens of interviews and chat-show appearances, so there’s still that air of inaccessibility that puts the star into movie-star. Compared to the other major actors of the moment, he has neither the model shop qualities of Timothee Chamalet, nor the bruising superhuman presence of Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson. Between these two extremes, it makes sense why he’s emerged as a popular figure.

The novelty of the film’s setting is reason enough for it to be interesting; the rural island is captured with menace and grandeur by director of photography Chayse Irvin, giving the impression that nature wields overwhelming authority over these characters. The opening shot, from the perspective of a drowning sailor, has no clear sense of identity, direction, space or time and roots the film in confusion.

Irritatingly, the ending is a tonal jolt that, in an attempt to end on a note of hopeful ambiguity, simply ignores the rustic unease of the previous ninety minutes. It’s an ending that fits, but in doing so misunderstands what made the rest of the film compelling. A fairly uninspired close-up of someone driving through the country lanes is boring next to grand landscape shots on untamed terrain, more at home in a family road-trip movie than a gothic chiller about the sins of the father. When faced with tying up their loose ends, the filmmakers opt for duct-tape.