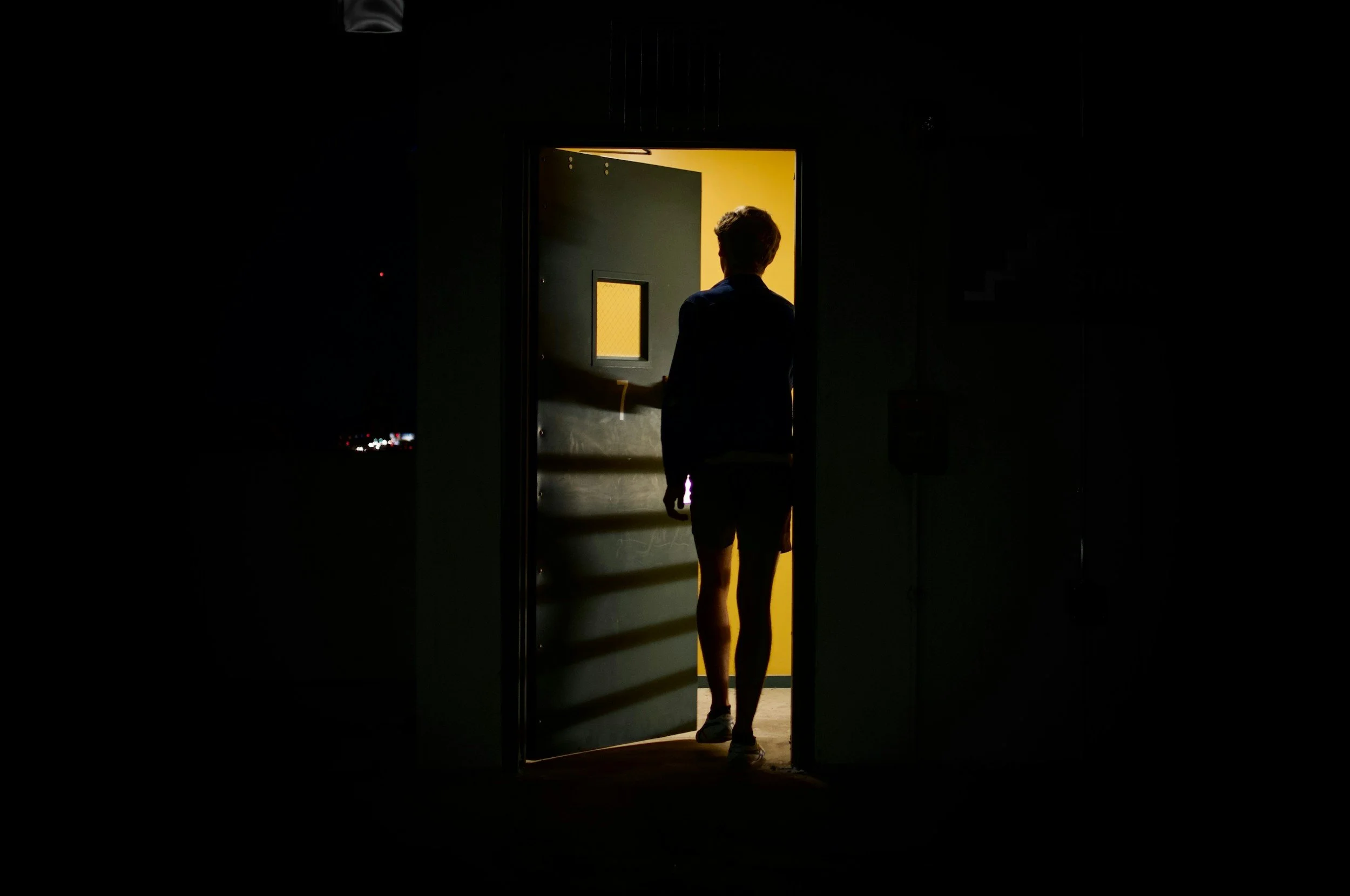

Re-entering the World: Why Prisoners Should Receive Free Therapy

Image Courtesy @mjearlb on Unsplash

Prisons are facing a mental health epidemic. Recent studies have uncovered a troubling reality: a significant number of convicted offenders have endured levels of trauma, abuse, and violence four times those experienced by the general population. According to the National Audit Office, as many as 90% of prisoners in England and Wales suffer from poor mental health, including conditions like PTSD and depression. However, only a shockingly low fraction—10-20%—of the most severe cases receive professional attention.

However, amidst this, there's a glimmer of hope—David Gussak, a researcher and art therapist, firmly advocates for therapy, particularly art therapy, for prisoners. His research demonstrates the effectiveness of art therapy in reducing recidivism rates: the use of art programs saw an impressive 80% decrease in reoffences six months post-release, and a 67% decrease after two years. Through creative expression, prisoners are provided with a means to confront their complex emotions and trauma.

In the UK, incarceration is the predominant response to criminal behaviour, resulting in the deprivation of individuals' freedom. However, alongside punishment, there should be a dedicated focus on rehabilitation. Offenders should be able to reintegrate into society after completing their sentences, but our justice system often fails to meet this expectation evidenced by a quarter of all released prisoners reoffending.

You may be thinking, “Should we really be prioritising rehabilitation? How would you feel if it was you or your loved one that was the victim?". Considerations of justice and fairness are indeed crucial - but our justice system should not be guided solely by this mindset. It is important to remember that incarceration itself is a form of punishment—prisoners lose their freedom as a consequence of their actions. Beyond numerous studies showing rehabilitation's effectiveness in curbing recidivism, an ethical imperative also exists. By offering opportunities for rehabilitation and support, we demonstrate our belief in the inherent worth, and potential for positive change, in every individual.

Certainly, when dealing with prisoners who have committed heinous acts and exhibit psychopathic tendencies, the path to rehabilitation may seem daunting, if not impossible. However, such cases represent a small fraction of the overall prison population - a recent study conducted in England and Wales found the psychopathy rates among prisoners to be as low as 7.7% in men and 1.9% in women. The overwhelming majority of prisoners, even those convicted of violent crimes, do not inherently possess violent tendencies. Rather, their actions often stem from a complex interplay of societal factors including poverty, homelessness, lack of education, or drug dependency. These are systemic issues that can be addressed through mental health interventions and support services.

Given the severe underfunding of the NHS and mental health services, you may question why prisoners should receive mental health assistance when many average individuals cannot access adequate services within the NHS. Yet, I posit that the mental health crisis in prisons is a direct consequence and an extension of this broader issue. The chronic underfunding of mental health services disproportionately impacts marginalised, lower-income individuals who are more vulnerable to incarceration. A recent study by the Centre for Population Change concluded that austerity measures led to a wealth inequality which both directly and indirectly increased crime in poorer areas.

Moreover, implementing therapy for prisoners has a strong financial rationale. Addressing mental health issues, particularly among younger inmates, can notably decrease their reoffending rates later in life. With the average cost of incarceration at approximately £40,000 annually, investing in prisoner therapy is both compassionate and practical. Studies show that most individuals display a natural decrease in violent behaviour after 35, indicating that providing therapy to young offenders might not only aid rehabilitation but also disrupt the cycle of crime, benefiting individuals and society overall.

The stark reality of the mental health crisis in prisons underscores the imperative of prioritising rehabilitation alongside punishment, both for ethical considerations and the overarching welfare of society. By investing in mental health support and therapy for prisoners, we not only foster individual redemption but also break the cycle of recidivism, leading to safer communities for all.