The Turkey-Syria Earthquake and the Limits of Science

In the wake of the severe earthquake that hit Turkey and Syria, seismic sciences can only go so far in predicting and preventing tragedies like these. So what exactly can it tell us?

Source: Unsplash

On Monday the 6th February, 21 miles west of the southern Turkish city of Gaziantep, the most violent earthquake to rock the region since 1939 erupted. As of writing, the death toll stands at over 46,000, but is expected to climb far higher.

As the people of Turkey and Syria wade through the ruins of their homes in an increasingly desperate search for survivors, we are left wondering: where did this earthquake come from, and could anything have been done to mitigate its effects?

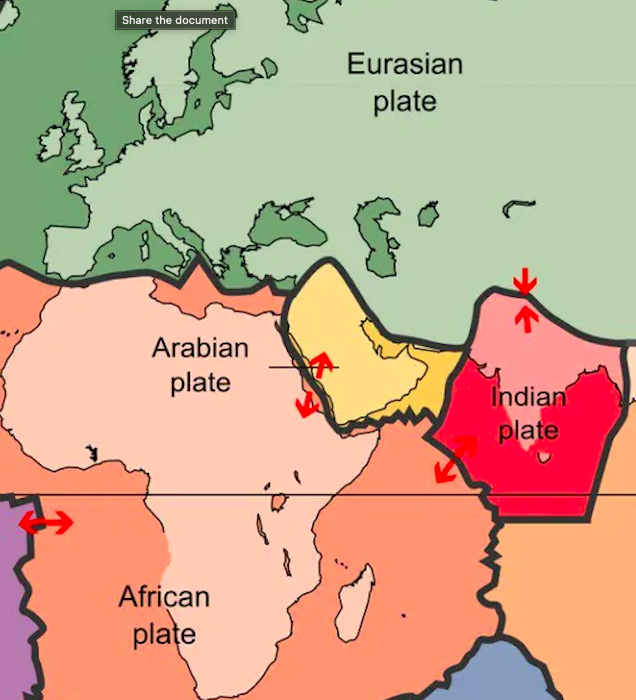

“Turkey is no stranger to earthquakes” says Dr Stephen Hicks, a research fellow in computational seismology at UCL. Indeed, Turkey and Syria finds themselves in a seismically active region due to the Arabian plate, a minor tectonic plate around Saudi Arabia, which is ploughing northwards into Turkey, at a rate of 11mm/year, “about the rate at which our fingernails grow”, Dr Hicks adds.

The collision is accommodated by two major fault lines: the North and East Anatolian faults. The former, which extends west from Istanbul, is where many of the historic earthquakes have occurred, including the Erzincan earthquake of 1939, but this year’s earthquake took place along the latter fault in an historically less active region.

Nevertheless, since scientists knew about the seismic activity of this area, was it not possible to predict the earthquake? “Sadly, we can’t predict earthquakes in the sense that we can’t tell exactly where and when they will occur and what magnitude they will be” explains Dr Hicks.

Though that hasn’t stopped some claiming that they can predict them. Frank Hoogerbeets made an extraordinary prediction of the Turkey earthquake in a tweet on the 3rd February, just three days before it took place. This claim, however, was based on the alignment of the planets, and whilst they occasionally appear accurate, if you’re making a prediction almost every week, some are bound to come true.

Monday’s devastation was further compounded by the shallowness of the rupture. Occurring at a depth of just 10km, the rupture propagated towards the surface causing cracks in roads and runways, one of the reasons why getting aid into the area is so challenging.

Of course, many of the fatalities from this disaster have been caused by falling buildings. At a magnitude of 7.8, older homes had almost no chance of staying up during the earthquake. However, newer buildings should have been able to withstand the tremors, according to the latest building regulations, but many now lie in ruins. This has incited great anger amongst people who now accuse building contractors of cutting corners and the government for not properly enforcing regulation.

Whilst it can offer little consolation for those reeling from the impact of this latest earthquake, can anything be done to mitigate the effects of future seismic tremors? Dr Hicks points to Earthquake Early Warning systems which are already in operation in certain parts of the world, such as Japan. They can detect low amplitude p-waves which arrive just a few seconds before the damaging s-waves. A few seconds' notice may not sound too helpful, but as Dr Hicks remarks “you wouldn’t want to be under the surgeon’s knife [when] an earthquake happens”!

But when it comes to dealing with the aftermath of the current disaster, there is little science can offer. Currently, border disputes between Turkey and Syria are hampering efforts to help thousands of wounded and homeless citizens causing a potential “secondary crisis”. It seems the resolution to this tragedy is more a question of politics than it is of science.

Update (21/02/2023): Another earthquake, of magnitude 6.4, has struck Turkey near the city of Antakya, close to the Syrian border. At least six people are reported to have been killed in the tremor which occurred at 20:04 local time, yesterday evening.