Tate Britain: "Women in Revolt!" Exhibition Review

Photo courtesy: Emily Whitchurch

Featuring over 100 artists, “Women in Revolt!” is Britain’s most exhaustive survey of feminist art to date. The exhibition’s six sections are bursting with British feminist history, spanning 20 transformative years from 1970 to 1990. Provocative and pensive, funny and furious, “Women in Revolt!” is crucially intersectional, exploring feminism’s inextricable links to race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, and health.

The art provides scathing criticisms across the political spectrum - “Tough!”, by the See Red Women’s Workshop, frames an unassuming portrait of Margaret Thatcher with text describing the nursery closures, unemployment, and economic strife her government facilitated. Meanwhile, Alexis Hunter’s “The Marxist’s Wife (still does the housework)” sheds light on Marx’s male-centric view of capitalist exploitation.

Section 1, “Rising With Fury”, launches us straight into the heart of the marches, protests, meetings, and attitudes that shaped 1970s feminist activism. At this time, marital rape was legal and maternity leave was non-existent. Chandan Fraser’s photographs from the first UK women’s liberation march in 1971 capture the fervent determination and optimism of its 4,000 attendees. Su Richardson’s “Bear it in Mind” features a pair of dungarees strained by the weight of domesticity, laden with endless to-do lists, cooking equipment, textiles, DIY tools.

‘Bear it in Mind’ - Su Richardson. Photo courtesy Tricia Teo

By the mid-1970s, some progress had been made in terms of workplace discrimination and employment opportunities. However, the personal was highly political, with many women producing activist art from their homes. Section 2, “The Marxist Wife Still Does the Housework”, invites viewers into the kitchens, bathtubs, and family photo albums of women artists. The work in this section is soundtracked to Gina Birch’s ‘3 Minute Scream’, where Birch screams directly into the camera on a loop: the pinnacle of female rage.

“3 Minute Scream” - Gina Birch. Photo courtesy Emily Whitchurch

A sensory feast, the screams and moans of Section 2 are replaced by feisty jazz music echoing from a television in Section 3. Named after the raucous X-Ray Spex song, “Oh Bondage! Up Yours!” introduces us to the rise of punk, postpunk and alternative subcultures in all their unapologetic glory. Established in 1981, the Neo Naturists’ manifesto is framed alongside exuberant photographs of naked, paint-covered bodies; they gleefully rejected the Thatcherite stoicism that dominated mainstream 1980s culture.

“The Maypole” - Wilma Johnson (part of the Neo Naturists). Photo courtesy Emily Whitchurch

Particularly striking are photographs of corporate billboards, each one graffitied by Jill Posener and her friends to subvert its misogynistic sentiment - capitalist consumerism was inevitably tied up in ideas of female objectification. One Fiat advert pictures a car, captioned ‘if it were a lady, it would get its bottom pinched’; ‘if this lady was a car she’d run you down’, the graffiti retorts. ‘By writing angry but humorous graffiti, we were also making the point that ad agencies don’t have the monopoly on wit’, Posener explains. ‘Graffiti creates a two-way communication’.

Moving into Section 4, “Greenham Women are Everywhere”, the feminist movement is confronted with issues of nuclear weapons and war. The Women for Life on Earth group formed in 1981 after nuclear weapons were stored at the Royal Air Force base in Greenham, Berkshire. The Greenham women were outraged at government spending on nuclear missiles rather than public services, extending their identities as mothers and carers to fight for the next generation. ‘The hand that rocks the cradle must also be the hand that rocks the boat’, says Sam Ainsley when describing her painting, ‘Warrior Woman V: The Artist’.

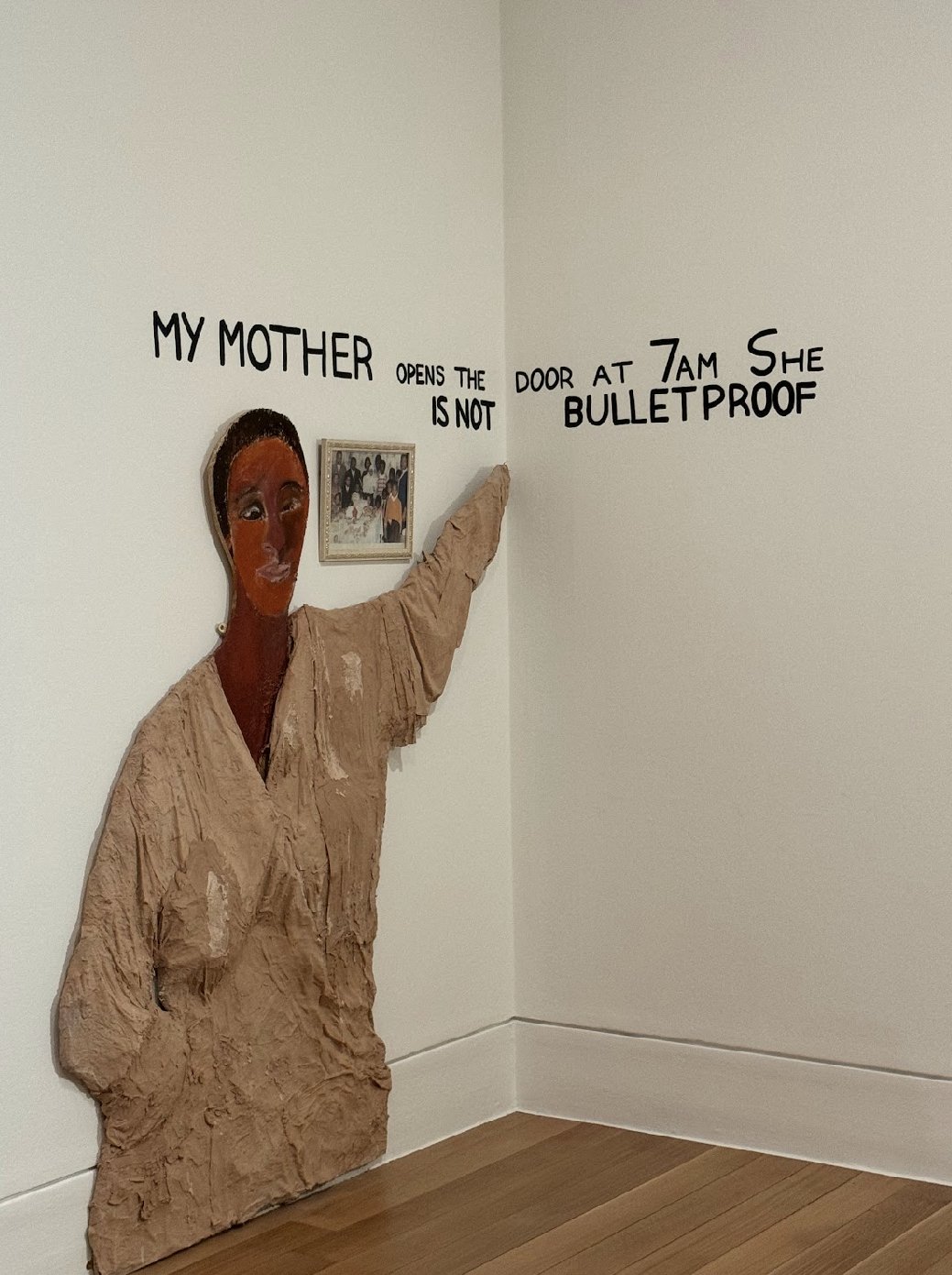

While some of the Greenham zines highlight the Black womens’ peace movement, Section 5 - “Black Woman Time Now” - finally casts the spotlight on Black and South Asian woman artists. Spanning two rooms, the art highlights the role of religion, colonialism, and community in the British Black Arts Movement. Marlene Smith’s “Good Housekeeping” installation depicts Dorothy ‘Cherry’ Groce at her front door, moments before being shot by the Metropolitan Police in 1985. On the wall, text reads: ‘my mother opens the door at 7am. She is not bulletproof’.

“Good Housekeeping” - Marlene Smith. Photo courtesy Tricia Teo

Finally, we make it to Section 6: “There’s No Such Thing as Society”. The art in this section completely subverts Thatcher’s infamous interview in 1987. In response to the introduction of Section 28, criminalising the ‘promotion of homosexuality’, Tessa Boffin produced “Angelic Rebels, Lesbians and Safer Sex”. Over the course of five photographs, an angel is enlightened by the discovery of lesbian safe sex practices, which were significantly overlooked during the AIDS crisis. One of the final pieces exhibited is Lubaina Himid’s “The Carrot Piece”, featuring a white man failing to tempt a Black woman with a carrot. Her hands are already full with the ‘self-belief, inherited wisdom, education and love’ that sustain her, uninterested in pitiful offers from white art institutions seeking to flaunt surface-level diversity.

Across the exhibition, women reclaim their bodies as vehicles for political and artistic communication. Penny Slinger dresses as an indulgent wedding cake, with the first slice cut to reveal her genitals; Rosy Martin wraps herself in slur-covered bandages; Helen Chadwick poses inside rigid domestic appliances - fridges, stoves, washing machines. Their bodies become agents, rather than subjects, defiantly subverting the heterosexual male gaze.

A photograph from “In the Kitchen” - Helen Chadwick. Photo courtesy Emily Whitchurch

“Women in Revolt!” sweeps viewers up into the urgency of second-wave feminism, flooding six sections of the Tate Britain with paintings, sculptures, photography, video, posters, crochet, poetry, zines; curator Linsey Young was keen to showcase a ‘constellation of voices rather than a few individual stars’. The sheer size of this constellation is astounding, as many of these artists have been ignored or intentionally overlooked in the mainstream art sphere for decades. Viewers are sure to be left with a profound sense of the tenacity of 1970s and 80s activists, though many of their demands still ring true today.

“Women in Revolt!” is on display at Tate Britain until 7th April 2024.