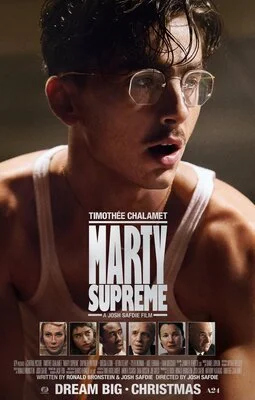

'It's Okay to Dream Big': Josh Safdie's Marty Supreme

Image via Wikipedia

Watching Josh Safdie’s heavily celebrated Marty Supreme, it’s hard not to notice the porous boundary between actor and character. Kevin O’Leary as the bulldozing tycoon, Gwyneth Paltrow as an aging movie star, and Timothée Chalamet as Marty Mauser, whose unabashed ambition is matched only by his perpetual kvetching.

The movie is best appreciated when considered within its star’s meta-textual context: Chalamet embodies Marty’s arrant devotion to his craft. Whilst accepting his Best Actor SAG award for A Complete Unknown, Chalamet declared he was “in pursuit of greatness”. He continues to speak of Marty Supreme with the same sentiment; “I hope this movie [...] can serve as that engine, that it is okay to dream big”.

The A24 epic propulsively follows salesman and part time ping-pong prodigy, Marty Mauser. Driven by an unshakable belief that he is destined for greatness, Marty enters into increasingly outlandish exploits to finance his international tournaments, armed with an unquestioning confidence and chutzpah.

The same earnest faith in imminent success is written into the film’s music. Despite being set in the early 50s, Safdie decided on a soundtrack consisting exclusively of 80s hits. The effect is disorienting, but situates Marty’s world as a place of estrangement, as if he is attuned to a future that no one else can comprehend. Much of the music Safdie selects (Forever Young most conspicuously) has the tonal sheen of a victory lap, glistening with buoyancy and triumph. Played over Marty’s pounding forward charge, it lends his ambition a sense of validation, as if greatness is already waiting for him in the future.

This unwavering belief in success is likely why the film lends so little attention to table tennis itself. We follow Marty through a car crash, a stolen dog, a shoot-out, multiple affairs, but very rarely do we get to see Marty hone his craft. What emerges is an ambition untethered from proof, where the only labour that justifies us rooting for Marty is the hope that there is some larger cosmic design; that all this damage was not done in vain.

The film is just as much a triumph of Jewish pride and resolve. Marty gleams that he is “the ultimate product of Hitler’s defeat”, embarking on what could be described as a Jewish-American Odyssey.

One of the most memorable scenes depicts Marty’s friend, Béla Kletzski’s interaction with Rockwell. Recounting the tender wounds of the Second World War, Rockwell finds out that Béla is a Holocaust survivor, and grumbles that his son was killed “liberating you people” (despite being posted nowhere near Europe). Marty asks Béla to recount a story from his time as prisoner, where — whilst disarming bombs for the Nazis — he came across a beehive and lathered himself in honey.

The scene culminates in a visceral image of men flocking to lick honey off Béla’s chest. Likely told for Marty to bask in some of Béla’s valour, the scene depicts something rare in the film: a moment of repose. Béla’s story is one of stopping and sharing, allowing his one moment of “freedom” to be beneficial to those suffering with him.

Thus, what ultimately undoes Marty is not his Jewishness, but his American exceptionalism. When the opening sequence depicted Marty’s microscopic impregnation of Rachel’s egg (which eventually metamorphosed into a ping-pong ball), the entire theatre erupted into laughter. Yet, as critic Bilge Ebiri writes in his review, the focalisation on the one sperm that manages to reach the egg hammers in the idea that “The world runs on for those who go fast, break walls, and never look back”.

Marty Supreme is charged, exhilarating and hyperkinetic — whizzing and whipping its audience around Marty’s singular frenzied quest for greatness. Yet the film refuses to make Marty’s narcissism feel consequential, as it culminates in Marty’s only durable achievement: fatherhood. The banality of the ending leaves you agape at the thrilling yet empty trip of Marty’s freewheeling lurch and crash from glory.