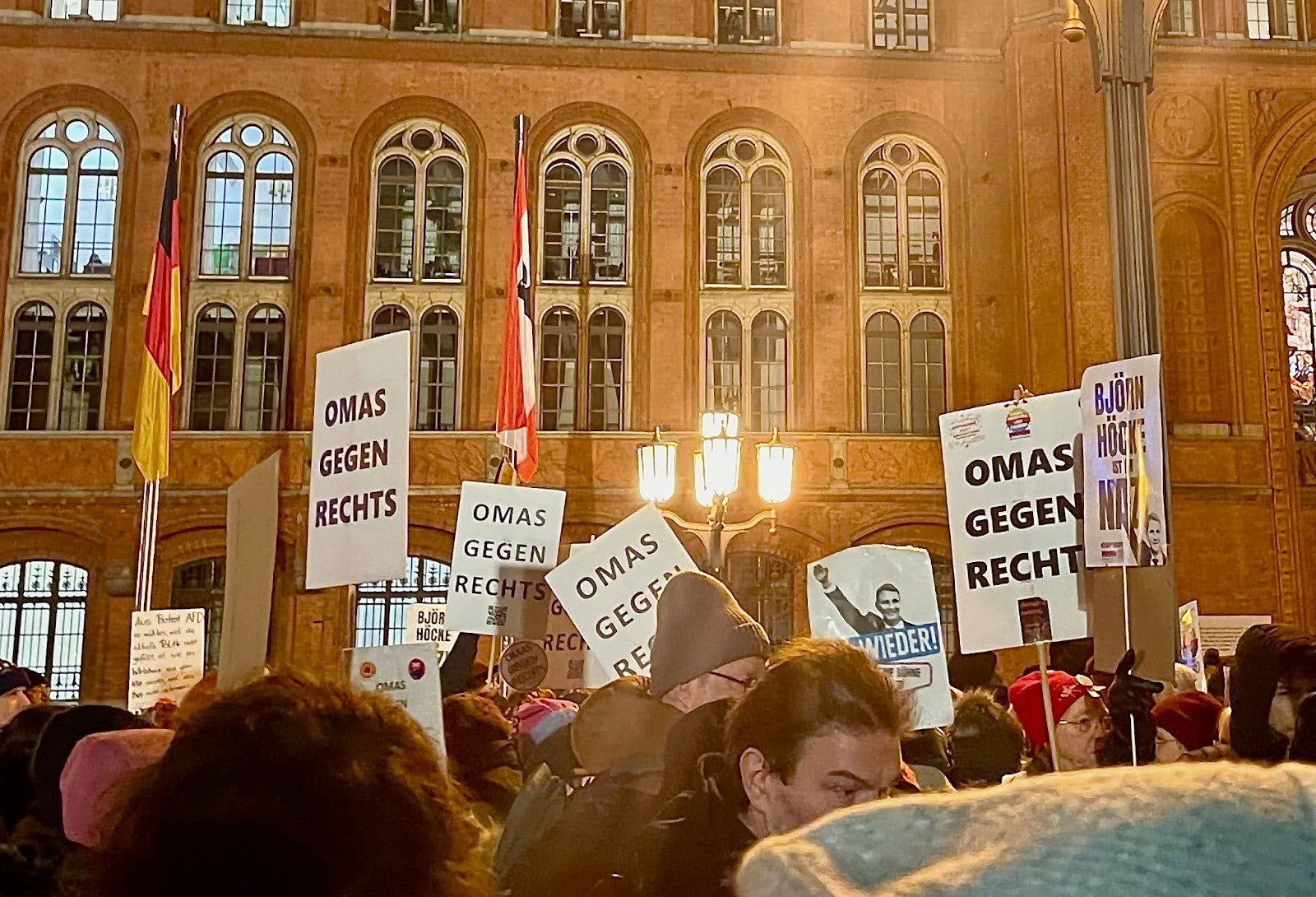

Protests Across Germany Against a Growing Far-Right

Photo courtesy of Isobel Knight

Last Wednesday, protesters gathered under the shadow of Berlin’s TV Tower; part of a nationwide movement against Germany’s far-right party, the AfD.

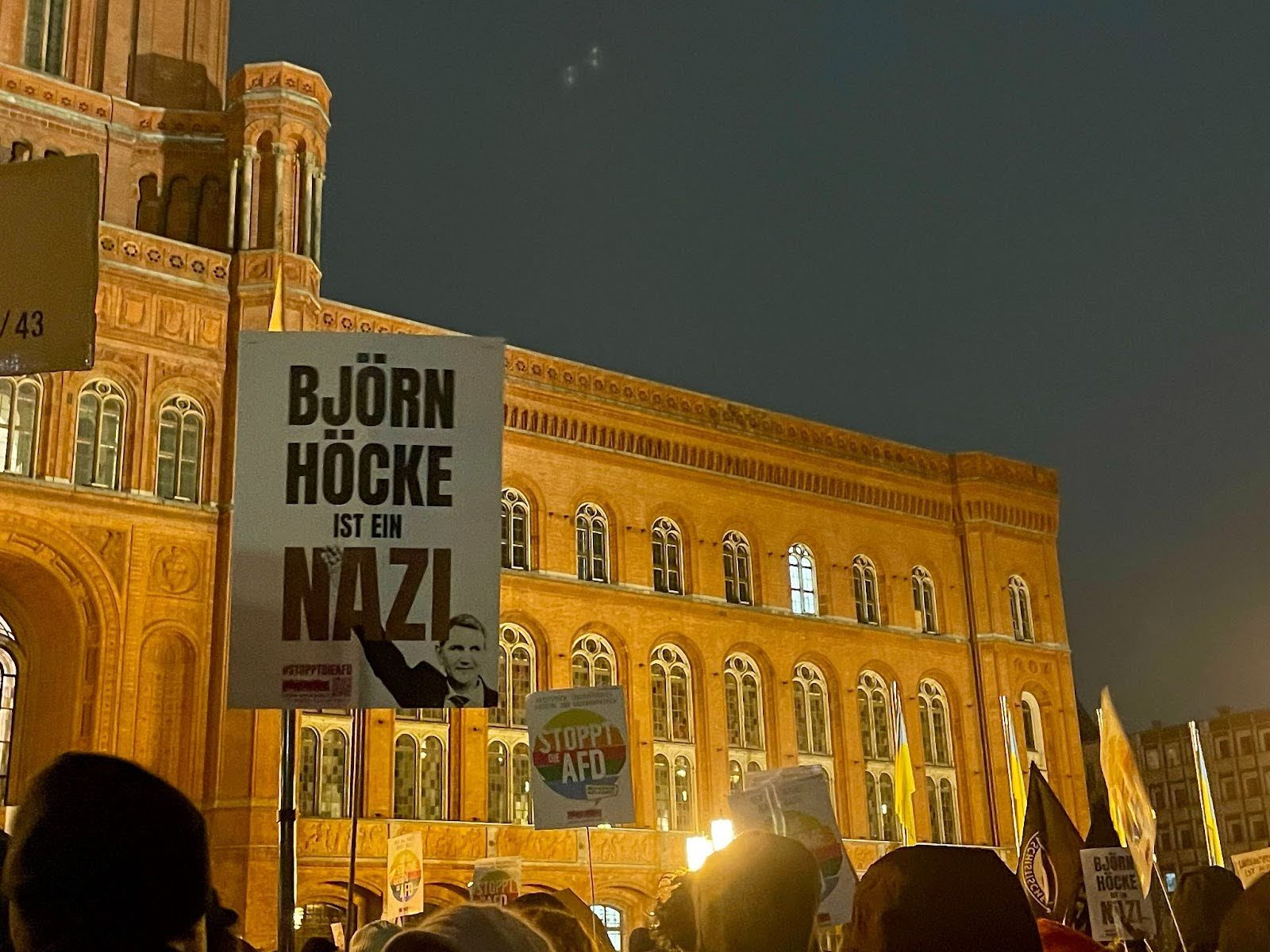

Image courtesy of Isobel Knight

The AfD – which stands for Alternative for Germany – was recently linked to neo-Nazi and radical far-right groups. Party members were found to have attended a secret gathering in Potsdam which detailed a ‘master plan’ for the mass deportation of immigrants and asylum seekers, including those with German citizenship.

Investigative journalists at Correktiv confirmed that AfD adviser Roland Hartwig was at the meeting, and he has since been dismissed by co-chair of the party, Alice Weidel – a decision which has caused contention within the party.

The AfD is openly anti-immigration and considers Islam a threat to German society. Proposed policies include bans on hijabs, mass restrictions on immigration, and a Brexit-style exit from the EU. They claim to promote traditional Christian values and oppose gay marriage.

Far from being a fringe group, they are currently in second place in the national polls and leading in the former East-German states of Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia, all of which are due to hold elections this year.

While hard right parties are usually associated with older generations, there is an alarming number of young voters backing the AfD; a phenomenon found across Europe, with Marine Le Pen and the Netherlands’ Party for Freedom increasingly popular amongst under 30s.

Protests calling to ban the party have taken place across Germany, including 100 demonstrations last weekend, both in major cities like Frankfurt, Berlin, and Hamburg, and in smaller towns. People held signs calling to ‘Stop the AfD’, and many drew comparisons to the Nazi party.

In Berlin, there were dozens of signs calling Björn Höcke – the AfD chair in Thuringia – a Nazi, in part due to his open usage of the slogan “Everything for Germany” in a 2021 speech – a phrase originally used by the Nazi’s paramilitary wing. He has also been critical of Germany’s attitude to its Nazi past; at a 2017 rally in Dresden, he said Germans are “the only people in the world to plant a monument of shame in the heart of its capital”, in reference to the memorial to Jews murdered during the Holocaust.

But can the AfD actually be banned? While it is possible according to German law, and many feel it is imperative, there are concerns that it could only strengthen the party’s popularity. Alice Weidel has used the proposed ban to criticise opposing parties, saying “the repeated calls for a ban show that the other parties have long since run out of substantive arguments against our political proposals.”

Some argue a ban against such a popular party would be undemocratic; others argue it is a necessary evil to protect the future of German democracy from the inside. Only two parties have been constitutionally banned in the nation’s history, one of them the neo-Nazi Socialist Reich Party, which was founded post-World War II.

At last Wednesday’s protest in Berlin, a crowd of people held Palestinian flags and signs calling out the hypocrisy of those vocally anti-AfD, yet silent about Palestinian rights. Germany, as a nation, is staunchly in support of Israel, in part because of a sense of responsibility after the Holocaust, and some argue this is using one genocide to justify another. Pro-Palestinian protests are banned across the country, and activists are regularly reprimanded for speaking out.

Instances of Islamophobia have increased in Germany since the Israel-Hamas war, and the AfD’s continued blaming of the nation’s issues on Islam and immigration is terrifyingly reminiscent of the Nazi’s early rhetoric against Jews and other minority groups.

Standing in the snow under Berlin’s Rotes Rathaus, a group of older women hold signs saying ‘Grandmas against the Right’. The fear of history repeating itself is perhaps more tangible to them than to anyone else.