The Privilege of Choosing to be Politically Disinterested

Image credit: Datarat17 via Wikimedia Commons

The ability to be consistently disengaged from politics is a form of privilege. It reflects a, perhaps unconscious, understanding that one’s life will not be majorly impacted by political changes. It assumes that laws were crafted with your best interests at heart, that the system will be there to catch you if you fall, that there will be opportunities readily available upon graduation, that your voice will always matter should you choose to share it.

Political apathy is on the rise. The UK’s 2024 general election had a turnout of just 59.7%, the lowest electoral turnout since 2001. And it’s not unique to the UK either; we’ve seen increasing political disengagement across much of Europe. For most people, this kind of political detachment is not an immediate sign of a socio-economic privilege, but rather the belief that politics has little bearing on their actual lives, and thus would be pointless to get involved in. Political apathy could also signal cynicism, or just complete and total ignorance. Or perhaps for others, it points to something more subtle: a kind of unspoken, implicit confidence. A confidence that, no matter how chaotic or disaster-stricken the government appears, or how unequally it distributes rights and protections, you know deep down you will likely come out unscathed, with your life not being radically disrupted by (and fairly insulated from) whatever happens in Downing Street.

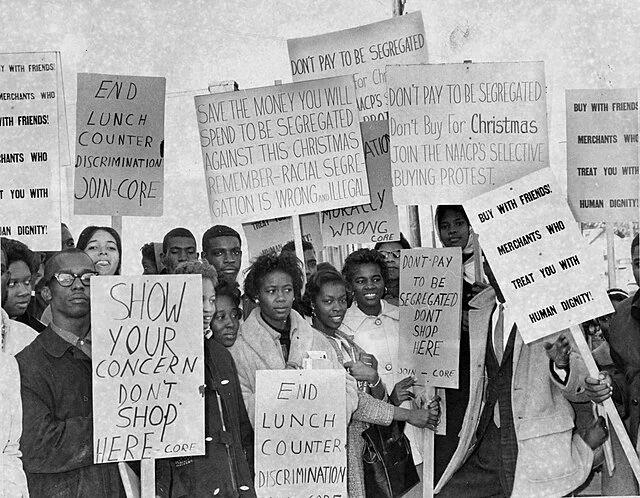

Not everyone has been afforded this privilege, however. Throughout history, there have been many instances of people rallying behind a political cause because their fundamental rights depend on it. During the Civil Rights movement in the US, for example, the fact that the very principles of personhood and equal citizenship were at stake meant many had no choice but to participate in political activism. We see this today too, most visibly in the case of transgender people, whose rights and legal recognition have become so politically contested that remaining disengaged is not an option.

Following the UK’s Supreme Court ruling in April 2025 that the legal definition of a woman is based solely on biological sex, enforcing the sex binary and allowing for knock-on effects in policing single-sex spaces, thousands of trans rights groups and allies took to Parliament Square to protest the decision. Over 100,000 people also joined the London Trans+ Pride in July this year, with its theme of ‘existence and resistance’ – a direct response to the Court’s ruling. Only recently was it announced that, as a result of the Supreme Court’s decision, trans girls can no longer join Girlguides, and from April, trans women will be excluded from the Women’s Institute – despite having been allowed membership for over forty years. It goes to show just how fragile rights recognition can be, especially amid the intensifying anti-trans rhetoric on social media, and how so many marginalised communities are not granted the privilege of political disinterest.

In this light, political apathy reveals less about individual indifference towards government, and more about unequal exposure to political consequences. To ignore politics is, in many ways, to benefit from a system that is systematically designed to protect you. We should confront the fact that, for many, participation is not merely a civic duty or virtue, but a form of defence and protection. Ultimately, understanding who can afford to disengage from politics – and who cannot – reveals the deep inequalities that continue to shape our political landscape.